|

|||||

|

The Robert Bowne Story |

|||||

| Introduction

Kaohsiung residents in need of relaxation or a visa may find themselves aboard a boat cruising up to Okinawa. About 150 miles east of the Taiwanese port of Suao lies Ishigaki Island, where the ship makes a call. Ishigaki Island is one of the Ryukyu Islands where many a shipwrecked mariner was kindly treated, a favour not always returned. Seemingly just a hilly blip on the typhoon map, Ishigaki has some interesting tales to tell, one of which is given here. The casual tourist with a few hours to while away on Ishigaki Island may well be directed out to the Tojin-baka, an imposing if secretive monument constructed in 1971 by the Ishigaki City Council. A tomb of Chinese design, the Tojin-baka serves as a memorial for some 300 Chinese 'coolies', or indentured labourers, who died on the island around 1852 and whose souls had long been respected by the islanders. This web-page aims to explore the story behind the Tojin-baka tomb (shown below) - a story that is often known as 'The Robert Bowne Incident'. |

|||||

|

The Tojin-baka Memorial on Ishigaki Island (Photograph courtesy of Chen Hong-da) |

|||||

| The Coolie Trade | |||||

|

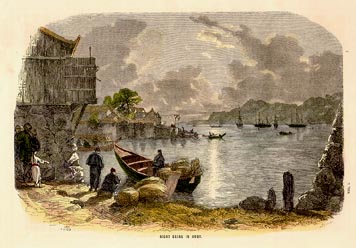

In the 1840s and 1850s Amoy was to become the

centre to a trade almost as pernicious as the African slave trade -

known as the 'coolie trade'. Originally,

the trade was operated through Manila merchants, but the flourishing trade

soon became dominated by the Amoy agency houses, such as Tait & Co,

and the British and American shippers.

James Tait, whose firm of Tait & Co was to become the largest shipper of coolies in Amoy, was also the Consul for Spain, the Netherlands and Portugal which enabled him to certify his own indenture contracts. The trade indeed depended on these contracts. |

A Night Scene at Amoy - Engraving ca. 1870 |

||||

|

|

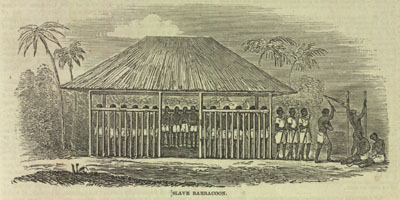

The agency houses first built

barracoons, known to the Chinese as zhuzi guan or ‘pig pens’, to store the human cargo.

These would have been very similar to the barracoons built on the West

African coast (shown left). They then paid

Chinese agents, known as crimps, to dupe or drug young Chinese males

into signing indentures and entering the barracoons where they were soon

abused and disciplined.

San Francisco and the California Gold Rush of 1849 proved a popular lure for the young Chinese male eager to escape the poverty and squalour of 19th century China. |

||||

|

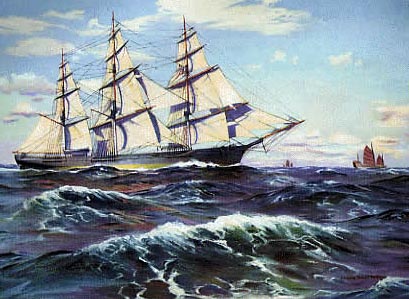

The newer and larger American

ships, such as the Westward Ho (shown to the right) flocked to the

trade.

These large ships were capable of taking hundreds of coolies on board, packing them just as tightly as the slaves from Africa. Their skippers and owners delivered the indentured Chinese to Panama, British Guyana, and Cuba in large numbers, but most notoriously to Peru. Off the coast of Peru lay the forbidding Chincha Islands where scarcely any rain fell. The coolies faced unremitting labour and almost certain death digging guano on the Chincha Islands where they frequently died under the whips of their Peruvian overseers or suffocated in clouds of guano dust. |

|

||||

|

|

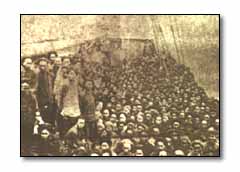

A contemporary Chinese labourer describes the voyage thus: “We proceeded to sea, we were confined in the hold below; some were … shut up in bamboo cages, or chained to iron posts, and a few were indiscriminately selected and flogged as a means of intimidating all others”. It is estimated that more than 10% of the ‘coolies’ would die on the voyage, with cholera being a particular risk. The ships themselves, known as coolie clippers, were built like convict ships with massive iron gratings to secure each hatchway and sometimes actual barricades with armed sentries across the ship. | ||||

|

|

|||||

| The

Robert Bowne Story |

|||||

|

A particular

hazard of the coolie trade was a mutiny at sea, where the crew would

certainly be outnumbered by the coolies if they escaped the ship’s

hold. One of the earliest mutinies was that on board the Robert Bowne

in 1852. The Robert Bowne departed from Amoy on 21 March 1852 under Captain Lesley Bryson of Connecticut with a cargo of over 400 coolies on board and officially bound for San Francisco. Bryson, from New Haven, had bought his ship for almost nothing in San Francisco. Although the official destination was San Francisco this was a subterfuge to deceive the local American and Chinese authorities: the true destination was to have been the dreaded Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru. |

|||||

|

The Chincha Islands (shown on the right) were notorious. With negligible

annual rainfall and crowded bird colonies, the islands had over the

centuries become massive repositories of guano. The guano was in great

demand as a fertilizer in the mid 19th century and commanded a high

price. The problem was to find anyone willing to mine the guano in such

harsh conditions.

The Chinese indentured labourers found themselves often tricked to go to the Chincha Islands to work for the Peruvian government. The ammonia-filled guano dust penetrated the lungs so that few workers survived more than one year, and the Peruvian Indians would not go there for any amount of money. |

The Chincha Islands in 1864 - Courtesy of David Rumsey |

||||

|

The coolies had

begun to die as soon as the ship left port from a combination of opium

withdrawal, seasickness and possibly cholera, compounded by the dreadful

sanitary conditions on board. Captain Bryson, worried over the dwindling

human cargo, decided to take action to halt the spread of disease and

assembled the coolies. Ten very sick coolies who could no longer walk

were thrown overboard to die, and the remaining coolies had their queues

cut off and were then harshly scrubbed down with brushes and saltwater. On 30 March 1852

a revolt broke out on the Robert Bowne. The coolies, resentful of

their treatment and believing that they had been deceived as to their

destination, rose up. In the resultant melee, Captain Bryson, his first

and second officers, and four crewmen were killed, along with ten of the

Chinese labourers. Though accounts

vary, it seems that the Americans retained control of the ship but ran

into a storm off the Ryukyu islands. The Robert Bowne was driven

onto a hidden rock offshore of Ishigaki Island on 8 April 1852 and was

stranded. The desperate crew, by now seeking only to save themselves

from the sea and the mutinous coolies, next forced all 380 remaining

coolies plus one Englishman into the sea to lighten the ship. Following the ship’s arrival back at Amoy the call for retribution was not long in coming. American and British ships were despatched to return the coolies to China to answer for the murder of Captain Bryson and his officers. |

|||||

|

|

An American ship,

the USS Susquehanna (pictured on the left at Naples in

1857) was

the first to arrive.

The Susquehanna, then commanded by Commodore John H Aulick, was the flagship of the US Far East Station based at Hong Kong, and arrived near the end of April 1852. The ship's crew managed to seize 69 of the Chinese on Ishigaki Island and transported them back to Canton where the US consul, Peter Parker, interrogated them. Through his interrogations Parker was able to find four coolies willing to testify against others. On this basis Parker found seventeen of the Chinese captives guilty of aggravated piracy and murder. Parker subsequently

handed over the seventeen to the Chinese authorities on 22 June 1852 for

punishment, rather inconsistently demanding both that they be tried ‘fairly and justly’, and

also that they be capitally punished. |

||||

| The Chinese authorities resisted Parker’s

urgings for capital punishment, claiming that this was a case of

‘buying and selling pigs’, the Chinese euphemism for the coolie

trade, rather than that of a revolt on an emigrant ship.

As the foreign crew members were barred from giving testimony due to lack of any legal precedent under the extraterritoriality that been imposed on the Chinese, Parker was forced to reveal his four Chinese witnesses. Under the new circumstances and under torture, the Chinese witnesses changed their testimonies and the Chinese authorities cleared all the accused except one. This one was simply admonished for pushing a crew member, causing him to fall overboard. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

The next ships to

arrive in the pursuit of the mutineers were all British, despatched by

British officials at Amoy to Ishigaki. The British were more direct in

their methods of rounding up the mutineers. A contemporary Ryukyuan

account describes how the British ‘went ashore armed and seized five

of the distressed people and shot three. Eighteen were frightened into

submission, three committed suicide by hanging, the rest fled and hid in

the mountains. The British barbarians then took the twenty-three

captured distressed people, as well as the one British barbarian on the

island, placed them on two ships, and on May 11 [1852] left, one after

the other. On May 22 another British barbarian ship arrived in pursuit,

arrested fifty-seven refugees, took them on board, and left. They also

said that later they would come back and seize all of them.’ |

|||||

|

King Sho Iku of the Second Sho Dynasty (born 1813, died 1847; ruled 1835-1847) |

The Ryukyu royal family, who were then still vassals to the

Chinese emperor and yet under strong Japanese pressure, feared that the British would indeed return and cause

grief to the island. The eldest son of the late King Sho Iku (pictured

on the left) sought the advice of the Ching court officials, when they

arrived aboard the tribute ships in 1853, on how to return the rest of

the coolies.

Under instructions from the Chinese officials, the Ryukyuans on 1 November 1853 sent two ships carrying the remaining 172 Chinese towards Foochow. However, pirates boarded the ships at sea and forty-seven of the coolies were spirited away, although three of these were later recaptured. The remaining 125 Chinese on the Ryukyuan ships arrived at Foochow on 14 November 1853. The local Chinese authorities examined the returning coolies and opined that these Chinese had not wounded or killed barbarians. However, the men were all sent back to their homes pending further possible investigation and punishment, of which no further record exists. |

||||

|

Even though the Chinese authorities failed to bring anyone to justice over the Robert Bowne affair, it was not through want of investigation. The Chinese magistrates spent over two years investigating the case, but it may well be that they sympathised with mutineers. Firstly, the coolie trade, known to the Chinese as ‘buying pigs’ was a violation of the Ching prohibition against emigration. Secondly, the cutting off of queues was strictly forbidden. Moreover, under the system of extraterritoriality insisted on by the Western governments the evidence of the ship’s crew was deemed inadmissible, and the Chinese witnesses were reluctant to testify at all. As to the Tojin-baka memorial on Ishigaki Island, it seems that perhaps 60 coolies perished there, though a similar number had probably died before the fateful arrival of the Robert Bowne in April 1852. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

The role of

Peter Parker (shown on the right), the US consul to China, remains enigmatic and

contrary. It should be noted that Consul Parker was also a great champion

of American involvement in Taiwan, which, with the shifting tides of

international politics, fizzled out in the late 1850s.

Commodore Aulick was subsequently relieved of his command of the Susquehanna and Commodore Mathew Perry took over the squadron. Perry was to 'open' Japan in 1854 aboard the Susquehanna. It can also be noted that it was the 1871 shipwreck of a Ryukyuan boat off the South Cape of Taiwan, and the subsequent murder of 54 Ryukyuan sailors from Miyako Island, which lies just to the east of Ishigaki, that precipitated the Japanese incursion into Taiwan of 1874. The Japanese demonstrated by this incursion that they were the true protectors of the Ryukyuans, which in turn led to the Japanese annexation of the Ryukyus in 1879 over the objections of the Ching court, who considered the Ryukyus to be a tribute state. |

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

Based on: Frederic Wakeman’s

address to the American Historical Association annual meeting in

Washington, D.C., on December 28, 1992. Published in the American

Historical Review 98:1 (February 1993): 1–17. Earl Swisher's 'China's Management of the American Barbarians', New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951. Gaddis Smith's 'Agricultural Roots of Maritime History', published in The American Neptune XLIV (1984), pp 5-10. |

|||||

|

|||||