|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Design | |||||||||||||||||

|

The

Japanese Still used in Taiwan was a modification of the original Japanese design to match the

conditions in Formosa and the experience with the Chinese Still.

Although the Japanese Still is usually said to have been introduced in the wake of the Japanese colonisation of Formosa/Taiwan, it is probable that its improvements were used earlier. |

|||||||||||||||||

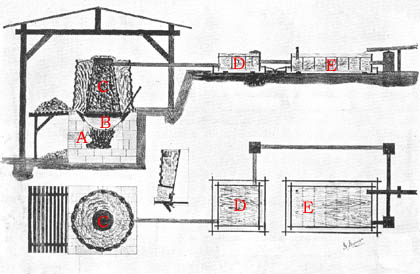

The

Japanese Still shown on the right is denoted as follows:

(Source:Formosa/Davidson) |

|

||||||||||||||||

| Photos | |||||||||||||||||

|

(Click on image to enlarge) |

The

thumbnail on the left links to a photograph taken in 1920 by Kirjassoff

entitled 'Placing Camphor Chips in the Chip Retort'.

In the full-size picture, two men loading chips into the top of the retort (C) and the fire-boxes (A) are visible. The other man shown is removing the 'spent' chips from the retort through an opening (F) that is sealed during operation. |

||||||||||||||||

|

A

second picture from Kirjassoff shows the crystallization-boxes (E) with

water from a spring flowing across them for cooling.

The bamboo used for piping at the stills can also clearly be seen. |

(Click on image to enlarge) |

||||||||||||||||

|

(Click on image to enlarge) |

In

another of Kirjassoff's amazing photographs originally published in the

National Geographic Magazine of March 1920, the condensed camphor is shown

on the walls of the crystallization boxes.

The boxes had typically six internal baffles to provide a greater surface for crystallization flowers. The camphor clinging to the boards is then scraped off and placed in tubs 'looking for all the world like so much snow'. |

||||||||||||||||

|

The

final thumbnail shows blocks of camphor placed on wooden troughs so that

the excess oil may drain off into the tin pails.

It is probable that the blocks have been formed in moulds or 'tubs', and that most of the Camphor oil, a yellowish essential oil, had already been drained off. |

(Click on image to enlarge) |

||||||||||||||||

| Process | |||||||||||||||||

|

The suitable site for the still is on sloping ground near a water source. The elevated part of the site allows the crystallization boxes (E) to be at a distance from and well above the top of the chip retort (C). Water, preferably from a spring, can then be channeled down in bamboo guttering to flow over the boxes, to enhance cooling and thus condensation, and into a reservoir for use in the water-pan (B). The site needs first to be cleared and a solid base prepared for the 'stove' or still itself. Structures are then built over the locations for the stove and crystallization boxes before construction begins. The stove consists of the fire-box (A) which is controlled by adjustment of the single opening for fuel. Above the firebox is the water-pan (B) which was about the size of a large 'wok', this is kept filled with simmering water through a small pipe from the reservoir. The volume of steam produced from the water in the water-pan is critical to the process and must be skillfully controlled by the fire keeper. On top of the water-pan is placed a perforated board and on this the actual chip-retort (C), which is encased within a second tapering cylinder with the gap filled with mud to seal and to insulate the still itself. The chip-retort typically narrows from two and a half feet at the base to less than a foot at the top, and stands about four feet tall. The steam from the water-pan is thus forced through the chips in the retort and out through a bamboo pipe sealed into the top of the retort. The average stove holds about 400 lbs (180 kg) of camphor wood chips and needs to be emptied and replenished each day. The bamboo pipe leads away from the top of the retort to the cooling (D) and crystallization chambers (E). The vapour from the stove is cooled both by the distance and by the water that flows over the tops of the chambers. A series of baffles within the crystallization boxes ensure that the optimal surface area is presented for the cooling vapour to form crystal flowers. The process is usually continued for a week to ten days after which the furnace is cooled and the camphor extracted from the crystallization boxes. The raw Camphor is allowed to stand and the yellowish Camphor oil to exude from the snow-like residue. The resultant Camphor and Camphor oil are then carried to market. |

|||||||||||||||||

| Yield | |||||||||||||||||

|

The

yield obtained from using a Japanese still in Taiwan is extensively

documented in 'The Island of Formosa Past and Present' by James Davidson (publ.

1903 by Kelly & Walsh).

Davidson reports that the real giant trees would measure 40 foot in girth and provide enough chips to operate a stove for several years. Large trees of 20 foot girth would keep a stove in operation for two years and yield some 50 piculs of crude camphor (6650 lbs or 3000 kg). As may be noted from the pictures the term stove may refer to several retorts (see Taxation). Kirjassoff gives a similar figure for the yield from an 'average' (12 to 15 foot girth ) tree in 1920, stating that its value would be around USD 5,000. This would be some USD 1,000,000 at present values. However street value and inflation are not always what they seem. On his calculation, the daily charge of 400 lbs of camphor chips would produce around 10 lbs of crude camphor, which would yield approximately 5 lbs of natural camphor and 5 lbs of residual crude camphor oil at the stove site when using a Japanese still. These two initial products would then be transported to factories either in Taiwan or Japan for further processing. Subsequently the yield would be about 4 lbs of commercial Camphor (cryst.), 2 lbs of Red or Brown Oil and 1.5 lbs of White Oil.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||