|

||||||

|

The Tale of the British Consulate at ShaoChuanTou |

||||||

|

"In 1858, China was defeated by the Anglo-French Allied Forces in the Second Opium War and compelled to sign the Treaty of Tientsin. In 1861, Robert Swinhoe, the first British Vice Consul to Taiwan, arrived at Takao from Amoy by gunboat. (In 1866), the official British Consulate was built." "In 1979, the Ministry of the Interior ... concluded that the Consulate building possessed an unusual value in the modern history of China as a concrete record and testimony of the presence of Western Powers in China. (The renovation) was completed in October 1986 (and) the Bureau of Civil Affairs of Kaohsiung City Government assigned a new role to the Consulate building by making it a museum of history and culture." [from 'The Restored Building of the British Consulate at Takao (1866-1910)' published by the Bureau of Civil Affairs of Kaohsiung City Government] |

||||||

|

|

||||||

| Introduction | ||||||

|

|

In front of the old British Consulate on the hill above Hsi-tzu-wan (西子灣)

at

ShaoChuanTou(哨船頭)

in

Kaohsiung

stands a

stone slab inscribed with graceful Chinese characters. This classical

stone stele expresses

the Chinese feeling of shame over the Opium Wars and subsequent foreign encroachments on Chinese soil and expounds on

how Kaohsiung's previous mayor, Wang Yu-yun, had proposed that the then-ruined building be restored as a monument to Chiang

Kai-shek's fight against foreign invaders and unequal treaties.

On the stele is further inscribed that 'this ShaoChuanTou British

Consulate building was established in 1866' and is thus the 'oldest

Western-style building (洋樓) ' in Taiwan. |

|||||

|

Inside the building is an interesting if eclectic collection of

photographs, models and charts dating back to the 1842 Opium War and

reaching up to the Sino-Japanese War of 1895.

Amongst these materials there are two interesting British documents, which are displayed together on the wall of what was once the British consul's bedroom. These are shown on the right in a picture taken in 2004. The upper document, which is a British Admiralty chart apparently dated 1865, shows the Consulate to be at its present position on the hill above ShaoChuanTou. The lower document shows an 1877 plan of the consular site with clearly visible handwriting to say that it was purchased on 22 January 1877 from one Lu Ta-tu.

This webpage aims to explore the apparent contradictions in the dating of

the consulate building, and to establish the probable actual date. |

|

|||||

| Early Days | ||||||

|

Robert Swinhoe (1836-1877) |

In June1861 the newly appointed

British Consular Official for Taiwan, Robert Swinhoe (shown on the

left), arrived aboard HMS Cockchafer at Takow under instructions to set up a 'Taiwan' consulate, though it was never clear whether 'Taiwan' meant Taiwan-fu (the capital, now Tainan) or the island of Formosa (Taiwan).

In fact, Swinhoe was intending to land at Taiwan-fu (Tainan), but was unable to do so due to the strength of the southwest monsoon in the open roadstead. Consequently Swinhoe did not tarry long in the village of Takow, then on ChiChin, after his arrival. He moved rapidly up from Takow overland to Taiwan-fu where he did indeed establish the first British Consulate on Formosa in July 1861. However by the end of 1861 the seemingly restless Swinhoe had moved further north to Tamsui where he believed most of the supposed trade to be centered. By May 1862 his health was apparently so weakened that he was obliged to return to England, where he was to deliver several famous treatises on Formosa and its wildlife during 1863 before again returning to Tamsui in February 1864. He was subsequently, in August 1864, ordered to return to Takow to set up the British Consulate. |

|||||

| Ternate | ||||||

|

Swinhoe arrived back in Takow in late 1864 and initially set up the British Consulate in quarters chartered by the British government

for six months aboard Dent & Co's receiving ship 'Ternate' in November 1864.

Other records show the ship as 'S S Clover', and it is very probable

that Swinhoe renamed the ship after Alfred Russel Wallace's essay

entitled 'Ternate'. Wallace is considered very much the "other man"

after Charles Darwin in the theory of natural selection, a subject in

which Swinhoe was both highly interested and influential. After 6 months 'mewed up' on the Ternate, Swinhoe rented a two-storey house 'from a rich Chinaman' on the southern shore of the lagoon at Chi-hou. One can surmise that this was as he awaited permission to construct a fitting consular residence on the recently-bought site at Freshwater Creek on ShaoChuanTou. |

||||||

| Freshwater Creek | ||||||

| In November 1864 Swinhoe, through an agent named Sun Kho, had obtained the permanent lease of a plot of land. This land is described as being 'situated at Freshwater Creek (Ta Shui Wan), Shaou-chuen-tow' with the Lagoon to the south. The site now lies behind the Kaohsiung Harbour Bureau building by the NSYSU tunnel, due to land reclamation in the lagoon. | ||||||

|

The newly-appointed British Minister to China, Sir Rutherford Alcock, in 1865 described the Freshwater Creek site to the British Foreign Office as being suitable 'for a convenient cemetery but fit for little else'.

In

1867, the site was further described by Major W Crossman, a British

government surveyor, as being ‘far

removed from the quarter where the

small business (at Takow) is carried on’. Thus Swinhoe was never

authorised to build on the site.

In

1871, Acting Consul William Gregory was permitted by the British

Minister at Peking to wall off a section of the Freshwater Creek site for

the burial of foreigners and to build a chapel thereon. Thus from

1871 a part of the site was indeed used as a Foreign Cemetery. Today the site has been occupied by squatters and few gravestones are visible. However, one remaining gravestone, shown on the right, is that of an Irish seaman named William Hopkins who was drowned crossing the 'Takow bar' in 1880. (For more on William Hopkins, click here.) |

Gravestone of William Hopkins (1856-1880) |

|||||

| Chi-hou Site | ||||||

|

There are various records that identify Swinhoe's 'rented' house as

being located at Chi-hou and as being the first British Consular

building. These documents include an old land deed, a letter that Swinhoe

wrote, a contemporary

painting and, especially, a British Admiralty chart.

The land deed refers to the permanent leasing of plot at Chi-hou in '1865 or 1866' by a certain Li Chai, who 'built thereon for the British subject Swinhoe, the said site being situated in the village of Chi-how on the shore of the lagoon'. |

||||||

|

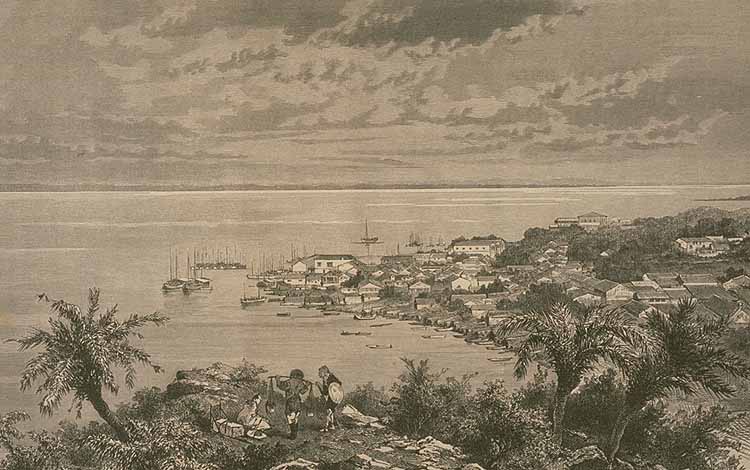

Collingwood's 1866 Painting 'from the Consulate' [From the collection of Paul Overmaat] |

The second document is a letter that Swinhoe wrote to the

British minister in Peking, Sir Thomas Wade, in August 1865. In the

letter Swinhoe laid forth his complaints about this first

shore-based consulate. Swinhoe described conditions at the house to be

most unsuitable, with 'the front ... used as a landing place for junks,

while it is also a favourite place for idlers and ruffians to lounge in'.

The building was visited by the British natural scientist Dr Cuthbert Collingwood in May 1866, and one of his paintings, notated 'Entrance to the harbour - Ta-kau (S W Formosa) from the Consulate' shows part of a substantial structure. This beautiful watercolour painting, shown on the left, is from the personal collection of Paul Overmaat. |

|||||

|

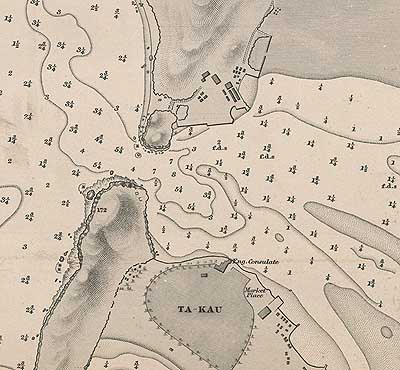

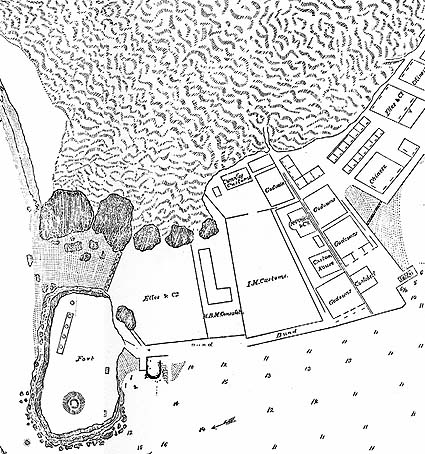

Perhaps the most convincing proof

that the first land-based British Consulate was on ChiChin comes from a British

Admiralty chart dated 1865, of which a detail is shown on the right.

On this Admiralty chart it can be seen that there was no building on the hill above ShaoChuanTou at that time, and that the 'English' Consulate is shown to be on ChiChin. Interestingly its marked position coincides exactly with the perspective from Collingwood's painting. The large building with extensive forecourt to the lagoon, just to the southeast of the market-place, is presumed to be the newly-built McPhail hong. This Admiralty chart is based on a survey made in 1865 by the British Royal Navy. The similar chart hanging today on the wall of the restored British Consulate is an updated version of the 1865 chart made in 1885, which explains why the Consulate is shown on the hill at that time. |

|

|||||

|

It was not until 1880, after the death of Swinhoe in 1877, that this lot was

sold. Acting on behalf of his widow, Christina, Jamieson Elles bought

the permanent lease for Elles & Co and it was later transferred to Tait & Co.

The second record mentioned above is the letter that Swinhoe wrote to Sir Thomas Wade in August 1865. In this letter Swinhoe had not only complained about the consular building, but also sought to persuade Wade to seek approval for the rental of 'the first strong well-built house' constructed at Takow for use as a fitting consulate. The house is described in detail by Swinhoe as being 'approached from the harbour by a substantial jetty, (with) on the right and left two long boarded rooms (of) 66 x 20 feet ... and two small rooms beyond'. The rental requested was excessive for Takow and no doubt Wade was obliged to refer the request to the Foreign Office in London, where Swinhoe was held in some esteem. The new building had been constructed, using Amoy materials and craftsmen, by McPhail & Co (see below - 'McPhail Hong Deed'). |

||||||

| Swinhoe's Departure | ||||||

| Swinhoe had been joined at Takow by his pregnant wife Christina and one child after his move to the building on the southern shore of the Takow lagoon. | ||||||

|

Mrs Swinhoe, as the only foreign woman, was fortunate that Dr James Maxwell

(shown on the right) was to arrive in 1865, before she gave birth. After the birth of this second child

in October 1865, Swinhoe, upon the advice of Dr

Maxwell, escorted his wife after her confinement to Amoy, where her parents were missionaries

and Swinhoe's brother-in-law was consul. In fact, Swinhoe was to remain nominally the Consul for Taiwan until 1873, though he returned to Taiwan only once, briefly, in 1868 to handle problems related to the camphor trade and missionary activities. |

Dr James Laidlaw Maxwell (1836-1921) |

|||||

| McPhail Hong Deed | ||||||

| McPhail & Co had permanently leased a site on Chi-hou in October 1864, and there is reason to believe that the building constructed thereon was the building to which Swinhoe referred in his letter to Wade dated August 1865. | ||||||

|

Detail from Collingwood's 1866 Painting of Chi-hou [From the collection of Paul Overmaat] |

There were very few structures of the size implied in Swinhoe's letter standing on Chi-hou in 1866 when Collingwood painted his view across the lagoon to Chi-hou, a detail of which is shown on the left. The first Consulate on Chi-hou, with flag flying, can just be seen in front of the small hill in the centre of the picture. Towards the left of the picture can be seen a large, long building. This distinctive building is almost certainly the McPhail hong. In

1867, a British Government surveyor, called Major Crossman, visited

Taiwan to report on the consular establishments. In his July 1867

report, it is recorded that the Consul had leased a building for five

years from a firm that ‘has become bankrupt within the last few weeks’.

The well-documented collapse of McPhail in May 1867 (see Pickering's

book), and the fact that the rental amount is precisely as proposed by

Swinhoe in his letter to Wade, leads to the conclusion that the building

is indeed the McPhail one. |

|||||

|

Due the firm's collapse in 1867, the rights were then transferred to Tait & Co in 1868.

Interestingly, the Chinese deed has

been annotated with the words 'Lease of British Consulate - to MacPhail & Co'.

From contemporary maps and Swinhoe’s description of the building it is possible to fix the location precisely. An 1875 engraving (shown below), after an 1871 photograph by Thomson, shows the presumed second Consulate at Chi-hou as the long pale building, with five windows running along its second storey, just to the right of the centre of the engraving. The building, which was still standing in 1944, has now disappeared. However, based on the five year lease, this would have been the British Consulate from late 1866 until late 1871. |

||||||

|

|

||||||

| Diplomatic Indifference | ||||||

| The British government decided to take a very passive role within the Ching Empire after the disturbances of 1868. These disturbances in Taiwan, which had seen fatal attacks on foreign missionaries and the burning of foreign missions as well as disputes over the camphor monopoly rights of the local circuit intendant (Tao-tai), had led to the very real use of gunboat diplomacy by the local British authorities. This confrontation was deplored by the British Foreign Office and led to the curbing of any such provocative actions in China. The British already had their hands full, and resources at full stretch, in containing a vast empire that included the vast Indian sub-continent and had no wish to precipitate the collapse of the Ching Dynasty. | ||||||

| As

a result, the early 1870s saw a very quiescent period in British foreign

policy. A period when the British were seemingly untroubled by the

rivalry of other nations, and sought only to pacify their own merchant

traders.

Much evidence suggests that the southern seat of the British Consulate was shifted up to Tainan (Taiwan-fu) from around 1871 until the telegraph line was completed between the Ching prefectural capital and the port of Takow in 1877. An 1873 plan of the extensive British Consulate located in a rented building beside the Ya-men (official residence) of the Tao-tai (Circuit Intendant or Prefect) in Tainan supports this view. However, with the return of the Benjamin Disraeli (shown on the right) as Prime Minister in 1874, the British were to take a much more assertive role in Asia: securing the 'coaling stations' for the naval and mercantile steamers; and seeking to stop the encroachment of other Western powers, such as Russia and the French. This led to a re-assertion of British interests in Formosa from the mid 1870s even though the extent and quality of the coalmines in Keelung had been largely discounted. |

|

|||||

| Consulate at ShaoChuanTou | ||||||

|

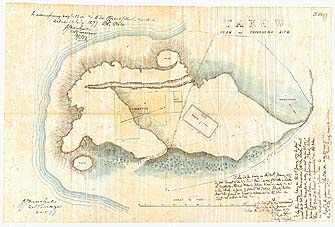

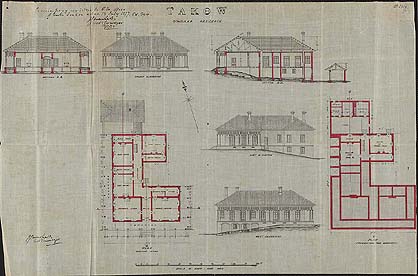

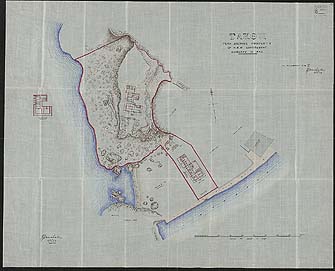

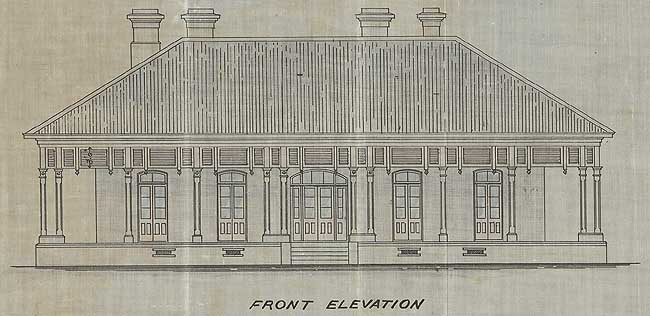

In January 1877 one Lu Ta-tu leased the site on the hill above Hsi-tzu-wan to Francis Marshall acting on behalf of Her Majesty's First Commissioner of Works. The plan of the

vacant site, shown

on the right, is dated July 1877 and was accompanied by the original architectural drawings for the Consular Residence,

shown below on the left. |

|

|||||

|

||||||

|

Note: The above three images are under British Crown Copyright and may not be used for any commercial purpose. |

||||||

|

The omission of the Consular Residence from the ICMC map of 1880 (with

detail shown on the right) suggests that the Consular Offices, shown as

an L-shaped building in the centre of the map, may have been built first, probably in the dry season of 1877/8.

This date of construction is further supported by a statement in

Coates' The China Consuls that a 'new consulate was built at Takow in 1878'. The number of bricks imported from Amoy in both 1878 and 1879 was just over half a million units. Although the present Consular Residence structure may use over three-quarters of a million bricks, the older structure, with its slender verandah pillars supporting wooden slatting, would have used fewer bricks. This suggests that the Consular Office and the Consular Residence were built in the consecutive years of 1878 and 1879. |

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

| 1900 Reconstruction | ||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Note: The above image is under British Crown Copyright and may not be used for any commercial purpose. |

||||||

| As has been mentioned, the original 1877 design (shown above) utilised slender pillars to support wooden lattice work. Although this may have been suitable for milder climes, the design was entirely unsuited to a building perched on a hill in a region prone to earthquakes and typhoons, let alone the depredations of termites. By 1899 much of the verandah area and the roof was on the brink of collapse, necessitating extensive repairs. | ||||||

|

Accordingly, in 1900 the exterior verandahs and roof of the building

were dismantled and the present design adopted.

The slender pillars were replaced with thick brick arching, and the external surfaces rendered with lime cement to resist the harsh saline atmosphere. The rebuilding work was carried out under the supervision of Robert Hastings who spent over 40 years in south Taiwan. The newer brickwork, which actually uses smaller bricks, can just be seen on the rightmost side of the consulate in this 1910 photograph. |

|

|||||

| Indeed the 1900 restoration seems to have been well carried out, for the old British consular residence seems to have survived in good condition until at least the late 1960s, as can be seen from the photograph below taken by an American sailor at that time. However, Kaohsiung was to suffer a catastrophe within a few years. | ||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The dramatic typhoon Thelma of 1977 caused very considerable damage to

Kaohsiung. Indeed the official record makes chilling reading:

"Thelma wrought more destruction on Taiwan than any event since

World War II ... During her rampage over Taiwan ... Taiwan's largest

harbor at Kao-hsiung was virtually destroyed. All eight giant cranes

used to load and unload cargo were badly damaged or destroyed. At least

17 ships capsized in the harbor ... ".

Typhoon Thelma may well account for the ruined condition of the British Consular Residence prior to its rebuilding 1n 1985 (see picture on right). The extensive restoration in 1985 was based on the 1900 design, which is its current appearance. This careful restoration was carried out under the supervision of Lee Chien-lang. |

|

|||||

| Conclusion There is thus little doubt that the British Consular Residence was built by the British Government in the dry season prior to May 1879, with the verandah and roof being rebuilt in 1900. Meanwhile, the search for the precise locations of

the two earlier British Consulates at Chi-hou continues and will be

reported on. |

||||||

|

The author acknowledges the generous help of Dr Yeh Chen-huei in the preparation of this article.

|

||||||

|

||||||