|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Part Two: The Wreck of the SS President Hoover |

|||||

|

Just after midnight in the early hours of 11 December 1937, one of the world's most luxurious cruise liners ran aground on Hoishoto Island (now Green Island) off the east coast of the Japanese colony of Formosa. The American ship was en route from Kobe in Japan to Manila in the US colony of the Philippines. Her name was the SS President Hoover, a jewel in the crown of the Dollar Steamship Line. A few days later the SS President Hoover was declared a total loss. This is her story and the story of the man behind her. |

|||||

|

The Wreck of the SS President Hoover

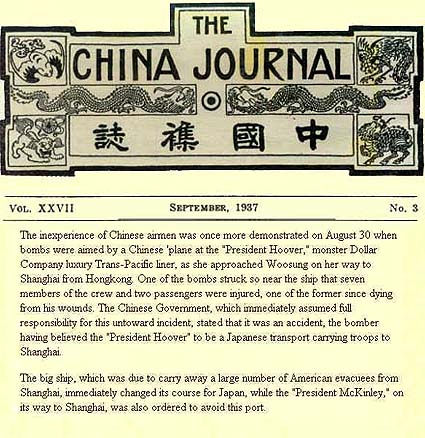

The year 1937 was to be a fateful one for both China and the Dollar Steamship Line, and particularly so for the SS President Hoover. The full-scale aggression by the Japanese forces, first near Beijing in July 1937 and then at Shanghai, effectively began World War II and ushered in a tumultuous period for the Chinese people. The Hoover's own troubles began on the 30th August 1937 in the Yangtze River, China. The USS President Hoover was at anchor in the Yangtze River, waiting for clearance to move into the Woosung River and up to Shanghai. Suddenly she was under attack by Nationalist Chinese warplanes, and, by the time the bombing had finished one crewman was dead, and another six wounded together with two of the passengers (see article from The China Journal below). |

|||||

|

It appears that the Chinese airmen had mistaken the Hoover for the Asama Maru, a Nippon Yusen Kaisha passenger/cargo ship of similar appearance, that was being used as a Japanese troop transport and was allegedly in the same area. This despite the fact that the Hoover reportedly had a 30-foot long American flag laid out on her top deck. Chiang Kai-shek, who had met Robert Dollar (see above), was furious, initially threatening to execute the officer responsible for this attack on his old friend's ship. The officer responsible turned out to be General Claire Chennault, the favourite of Chiang's wife Soong Mei-ling. His life was spared and indeed Chennault was surprised to receive a $10,000 bonus from Chiang soon afterwards. One of the Hoover passengers, a 17-year-old named George Ow Sr., later related how he almost did not reach America. As the Japanese troops bore down on southern China in 1937, Ow's adoptive father had put him aboard the USS President Hoover in Hong Kong with just $10 in his pocket. Ow recalled that although the ship had sustained only minor damage, she had "to limp into San Francisco". |

|

||||

|

After her repairs, the USS President Hoover had set off again in late November 1937, under

the 65-year-old Captain George W Yardley, across the Pacific bound

for Kobe and Manila. Reportedly, due to the lingering effects of the

1936 Maritime Strike, most of the crew were inexperienced seaman, later

described by passengers as 'last minute pickups from West Coast hiring

halls'.

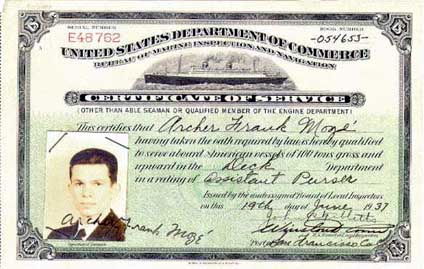

Setting out from Kobe with 503 passengers and 330 crew, the SS President Hoover followed an unfamiliar course to Manila. The normal course would have taken her to Shanghai and down the Taiwan Strait, on the west of Taiwan, to Hong Kong. The Dollar Line was now avoiding the port of Shanghai and, with an inexperienced crew, was proceeding at night down the unfamiliar and unlit eastern coast of the Japanese colony of Formosa (Taiwan). On board the USS President Hoover were two young Assistant Pursers, Eugene Lukes and Archer Moze (see Certificate with photograph below). Their version of events is recorded on the website of American President Lines. Gene Lukes begins the story. |

|||||

|

|

"It was wintertime and a strong monsoon was blowing. The Captain

was getting these messages, 'You must be in Manila, absolutely urgent

that you arrive not later than 6 a.m. such-and-such a date, make all

possible speed.' Maybe an afterthought with due regard to safety."

"We were zooming along southward to the eastward side of the island of Formosa, Taiwan now of course, controlled by the Japanese, who had turned out all the navigation lights. So we were sailing on what was called dead reckoning." |

||||

|

Lukes continues, " Well, winds and seas are not always that predictable, and about midnight we came close to shore and hit a peninsula. Arch and I were in bed, and I felt this bump and said, ‘Arch, we’ve run aground.’”

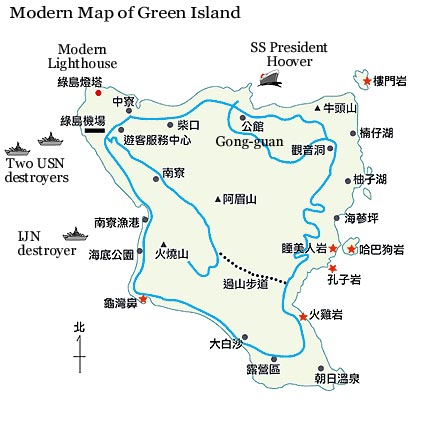

Moze says, “I’ll tell you what, the deck crew was out washing the deck and they were dropping things, making noise and keeping me awake, and then all of a sudden we heard, boom, boom, boom, like that. Then all of a sudden it stopped, quiet. We didn’t have radar on the ship in those days and it was very misty, you couldn’t see anything. If we’d gone a little further out, we’d have hit this big rock head on and sunk entirely, so we were lucky.” The USS President Hoover had run hard aground on a reef off the north-east coast of the Formosan island of Hoishoto [火燒島] (also known as Samasana Island, Kasho-to, now Green Island [綠島]) at 1 am in the early hours of 11 December 1937. (For location of the stranding see Map below). |

|||||

|

Captain Yardley ordered an SOS to be sent out for assistance, and flares

to be fired. The SOS was received by the German freighter Prussia

which arrived around dawn, but, as the waves were still very large,

there was little she could do to help.

Moreover, the loud noises that the Hoover had made upon grounding and the brilliance of the flares had initially frightened the islanders, who, believing that a war had begun, fled into the nearby mountains. It was not until dawn that the islanders saw the stranded Hoover and came down to help. |

|

||||

|

"After the grounding," Lukes continues, “sure enough the general alarms went off, and we were getting all the passengers out, getting everybody up on deck. It was blowing, the seas were starting to smack against the side of the ship, it was pitch black. And pretty soon we could see little bobbing lights along the shoreline, little oil lanterns so we obviously stirred up the natives. As it got lighter we could see that we had ripped out the bottom almost clear back to the engine room. There was a lot of oil, and it oiled the sea and the beach. There was no backing off, so we had to get the passengers ashore. We lowered the lifeboats with people in them." |

|||||

|

|

Lukes mentions 'a lot of oil', and it appears that the Hoover initially

tried to float itself off the reef by jettisoning fuel oil and cargo to

lighten the ship.

However due to strong winds from the Northeast monsoon and the large waves, the Hoover was merely driven further onto the shores of Green Island: whereas she had grounded 500 metres out, she soon lay just 100 metres offshore and had begun to list badly. At low tide around 1 pm, Captain Yardley ordered the evacuation of the passengers. The islanders, now able to get their motor fishing boats near the wreck assisted in disembarking the passengers through the oily waters to the shore. |

||||

| More from Lukes: “We had the natives with their boats helping us. We put a line ashore and then with a winch we could bring the line so it didn’t sag down into the water. With crew members holding each end of the boat onto the wire with heavy gloves, you could keep the boat pointed in the right direction.” Moze says, “I was the first person ashore. Believe it or not. Mr. Holzer, the Chief Purser, told me to go ashore and handle the passengers. So I grabbed an oar and those damn lifeboat oars were so big I could barely get my hands around them. Anyway, it took about fifteen minutes to get ashore, it was so rough. Some of the women passengers were reluctant to go into the oil, so the crew would just pick them up and put them ashore." | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

A contemporary report in the 27 December 1937 edition of Time

magazine gives a somewhat different version of events.

The Time article reports that Captain Yardley had initially played down the extent of the disaster. The article further relates how, according to passengers, the inexperienced crew had capsized two lifeboats in shallow waters trying to land the line, though all the passengers were landed on the island within 36 hours of the line being secured. |

|||||

|

|

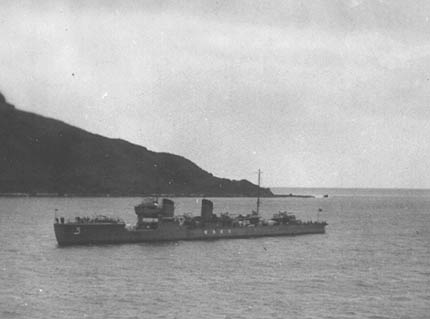

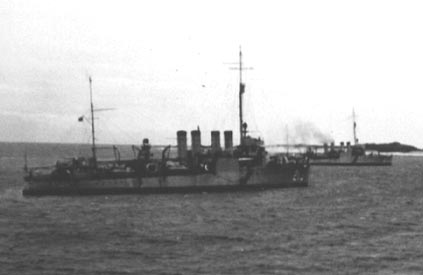

During the course of that first day at around 3 pm the Japanese Myoko Class heavy cruiser IJN Ashigara [足柄] and an unidentified Mutsuki Class destroyer (shown left photographed off Hoishoto) appeared on the scene to observe and protect the Hoover. Meanwhile, on board the Hoover an unruly group of crew members had reportedly broken into the ship's bar and begun to party. Passenger accounts then relate how this carousing sailors then resolved to pay a visit to the passengers on shore on the night of the 11th December. According to the article, the 'liquored seamen (then) began hunting for women', whereupon some Hoover officers and passengers formed a vigilante group to protect them. |

||||

|

The passengers later complained that there would

have been no such disturbances if the Japanese police had earlier

allowed the Hoover officers to come ashore with guns. It may

well be that the Hoover officers had other worries.

The USS President Hoover was a US mail carrier and carried the registered mails, which were kept in 'specie tank', which got its name from the large amounts of gold and silver bullion stored there. According to Gene Lukes, “It was a big safe with a big steel door and a combination lock and big locking bars across it with big padlocks on it. The Chief Mate had keys to the padlocks and the Purser had the combination to the safe. What did we carry in the specie tank? Well, we carried registered mail. You never knew what was in registered mail, transferable documents, negotiable instruments, stocks, boxes of paper currency, gold and silver bars and coins, that’s the way they were moved in those days. Banks settled their differences and balances lots of times with movements of gold or silver.” |

|

||||

|

Lukes’ task aboard the grounded Hoover reflected the sense of danger. “Mr. Holzer [Chief Purser] sent me to the first class smoking room where the slot machines were. There were nickel, dime and quarter slot machines, quite a revenue for us during those days, though they were locked up in the United States. I emptied the slot machines and had all the money in two canvas money bags about the size of a two or three pound salt sack. So I strapped that around my waist so they wouldn’t hamper me and then Jeff Holzer gave me his pistol. These were the days of piracy and you never knew whether you would have an uprising among your 400 steerage passengers. Anyway, when I jumped out I jumped right into a hole in the coral and I went right down. Fortunately the wave receded and I surfaced again, and they pulled me ashore. I was pretty well oiled, but I kept that money, guarding it with my life with Jeff’s pistol.” |

|||||

|

Due to the importance of the US mails aboard the SS President

Hoover and in order to protect the US ship from 'interference' from the

Imperial Japanese Navy, help was urgently requested from the US Navy.

In the early hours of 11 December 1937, the US Navy destroyers USS Barker and USS Alden received orders at Manila to proceed immediately to the aid of the stricken Hoover. At 12.45 pm on 12 December, the USS Alden, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Stanley M Haight, sighted her destination, Hoishoto, and requested permission from the captain of the IJN Ashigara to enter Japanese territorial waters. The USS Barker arrived shortly afterwards whereupon a Japanese naval officer boarded the Alden to formally grant permission on behalf of the Japanese government for the two ships to enter Japanese waters to assist the SS President Hoover. |

USS Barker (DD-213, foreground) and USS Alden (DD-211) photographed off Hoishoto |

||||

|

The Alden promptly sent a guard of two officers (Lt Comdr Haight and

Ensign John H Parker) and fifteen men to guard the Hoover's specie

tank. Armed men from the two naval ships were also sent on shore to put

an end to the unsettled situation prevailing there between the

passengers and, allegedly, some of the Hoover's crew.

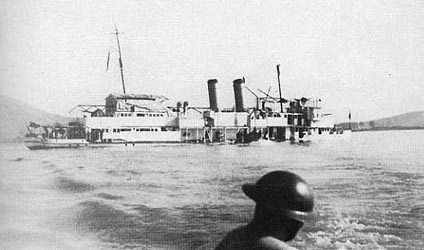

At 3 pm on 12 December, a Japanese ship, the Toriyama [鳳山], arrived from Keelung [基隆] carrying food and other necessities for the crew and passengers of the SS President Hoover. On 13 December the SS President McKinley arrived and the following day departed to Manila carrying 700 passengers and crew. As Moze recounts, " The passengers were there two nights and they were taken off by the President McKinley and taken to Manila." |

|||||

|

A SS President McKinley boat embarking passengers from the Hoover |

|||||

|

|

Tensions off Hoishoto were to heighten on the morning of 14 December,

the day that the SS President McKinley departed for Manila.

News came through about the bombing by Japanese aircraft and sinking of the USS Panay in the Yangtze River on 12 December. After most of the staff from the US Embassy at Nanking had been evacuated in November 1937 in the face of Japanese advances into South China, the gunboat Panay had been ordered to remain nearby to provide protection and to evacuate the remaining US Embassy staff 'at the last possible moment'. |

||||

|

The last US Embassy evacuees came on board 11 December and Panay moved upriver to avoid becoming involved in the fighting around the doomed capital.

On 12 December, Japanese naval aircraft were ordered by their Army to attack "any and all ships" in the Yangtze above Nanking. Knowing of the presence of Panay, the Navy

had requested and received verification of the order. The Panay (see

above left) was duly attacked and sunk. Three men were killed, 43 sailors and 5 civilian passengers wounded.

The USS Alden was ordered to break out and stow in her ready racks 47 rounds of 4-inch service ammunition during the forenoon watch on 14 December as a precautionary measure. However the alarm seems to have been unwarranted and the Japanese authorities handled the situation both professionally and cooperatively. |

|||||

|

On the next day the SS President Pierce arrived and embarked the

remaining crew members from the Hoover, including Archer Moze, departing on 16 December.

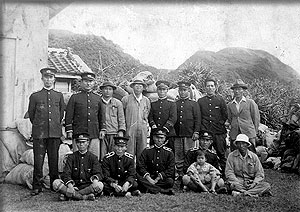

The USS Alden remained off the island until 23 December 1937, after which the USS President Hoover remained under the guard of the Japanese police who had established a base at the stone house of a Mr Liu Ting-kun [劉鼎坤]. The contemporary photograph on the right shows the Japanese police guard with Gung-guan Head [公館鼻] in the background. |

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

In February 1938 the SS President

McKinley returned to Hoishoto carrying Chinese labourers (coolies) to

carry out salvage operations on the stricken Hoover, which was by now

assumed to be a total loss.

The Japanese authorities set up a shore base (see photo above) to cooperate in the salvage operations. |

|||||

|

Once Dollar Lines had completed their salvage work, it was clear that

the SS President Hoover was indeed a total loss. As a result the hull

was sold to the Kitagawa Ship Salvage Company [北川打撈株式會社]

for $500,000.

It would take three further years to clear away the wreck of the SS President Hoover. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

| The End of the Story | |||||

|

|

The fateful year of 1937 proved to be the beginning of the end one for the Dollar Steamship Line. Though the company had survived the Great Depression, it had suffered great financial strain. In June 1938 the SS President Hoover's sister ship, the SS President Coolidge, was arrested in San Francisco for an unpaid debt of $35,000. She was released on bond for her last trip under the Dollar flag across the Pacific. The Dollar Steamship Line was suspended from operation. | ||||

| A 1937 investigation by the Federal Maritime Commission, under Joseph P Kennedy, had targetted the Dollar Line and its financial arrangements with the US government. | |||||

|

Eventually the Dollar family bowed to the inevitable: the ownership of

the Dollar Steamship Line passed to the US government in exchange for

the cancellation of its debts. As part of the deal, the name

"Dollar" was no longer to be used and all the senior level

staff were removed. In August 1938, the Federal Maritime Commission took

control of the company.

On 1 November 1938 the name of the company was changed to the American President Lines. In the place of the "$" logo that had graced the funnels of the Dollar ships, the new symbol was a white eagle. |

|

||||

|

|

On today's Green Island, the lasting memorial to the Hoover wreck is the

lighthouse on Pi-tou-chiao [鼻頭角].

In 1938, the residents started to build a lighthouse, designed by Japanese engineers and financed by public donation through the American Red Cross. No doubt the islanders hope that this 33-meter high beacon for mariners will ensure that their peaceful slumbers are never again shattered by the terrible grating of a huge ocean liner on the reef of Chung-liao Bay. |

||||

|

|

|||||

| Notes:

The Hoover was not the only famous wreck at Green Island. In March 1864, the British brig Susan Douglas was wrecked on the island (then known as Samasana) while swept off course on a voyage from Hong Kong to Ning-po. The captain and crew were treated kindly by the islanders, who looked after them for more than a month. The captain travelled back to Takow (Kaohsiung) by junk; the others, with the exception of a Hawaiian who died on the island, were rescued by the British gunboat Bustard under Lieutenant Tucker. (Davidson) Much more information about the Dollar Steamship Line can be found on the website of American President Lines, its eventual successor. Extensive use has also been made of Michael McFadyen's Scuba Diving site, which contains much information about the SS President Hoover's sister ship, the SS President Coolidge. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||