|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| The Japanese

Counter-Attack The Japanese garrison at Tung-kang was mobilised on the night of 29 December 1898. However, due to disrupted communications, they marched north towards Chao-chou rather than south towards Heng-chun. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Japanese troops searching for rebels |

In order to break the siege of Heng-chun [ 恆春鄉 ] and restore order, two detachments of Japanese troops were sent south by sea from Tainan's Anping [ 安平 ] port on 29 December. However due to poor weather conditions they were forced to make a difficult and delayed landing at Che-cheng [ 車城鄉 ] nearly ten kilometres north of Heng-chun, on 31 December 1898, rather than the planned landing at Ta-wan Bay just to the south of Heng-chun.

From Che-cheng the Japanese

troops marched towards Heng-chun. After securing Heng-chun, the Japanese military then launched a major sweep up through the south-western Taiwan plains searching houses and following leads no matter how spurious they might be. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Japanese forces methodically and

ruthlessly hunted down and killed all people that

were in any way connected with the southern insurgency. The methodical sweep by

the Japanese military resulted in over 2,000

people being killed in the following three months to March 1899. International protests followed the reports of Japanese massacres in southern Taiwan which resulted in a sudden change of strategy. It was now clear to the Japanese that it was in practice impossible to impose a purely military solution to the problem of insurrection and banditry in the south of Taiwan. Although the insurrection in Taiwan had begun as nationalistic rebellion, it had seemed to have given way to mere banditry and lawlessness. The military campaign in south Taiwan served at least to prove that the so-called 'Triple Guard System' of Governor-General Kogi, whereby suppression of 'banditry' was a purely military affair, was too crude and that a new system involving a civilian police system and the 'ho-ko' system which was essentially a reinstatement of the old Ching 'pao-chia' system, by which one village leader was responsible for all the villagers' good behaviour, were necessary. Although the military sweep had certain bludgeoned down the resistance it was hardly 'scientific' which was term preferred by the new de facto Japanese ruler Goto Shimpei. Moreover, Lin Shao-mao and his new ally Lin Tien-fu remained at large. |

A mass grave for victims of the Japanese massacres in southern Taiwan |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Baron Goto Shinpei ( 1857 - 1929 ) Chief of Civil Administration in Formosa |

Japanese

Clemency

In !898 the military rule of Taiwan had effectively been changed to a civilian administration under the new Governor-General Gentaro Kodama and his chief of civil administration Goto Shinpei. General Kodama was a military man yet placed full trust in his close colleague Goto Shinpei who became the first civilian administrator of Taiwan and progressively its real ruler. Goto Shinpei, who believed in a 'scientific' approach to governance was to effectively rule Taiwan from 1898 until 1906. Indeed, Goto is considered by many to have been the true modernizer of Taiwan. International pressure in 1899 reinforced the civilian governor Goto Shinpei’s hand against the previously military solutions to the crisis, and the Japanese policy towards insurrection in the south of Taiwan was changed. Goto and Kodama had already put into effect a mechanism whereby 'brigands' might surrender to the Japanese virtually on their own terms. This policy was on the supposition that many ‘bandits’ were in fact honourable nationalists and not mere robbers. At least in this way the ‘bandits’ could be clearly identified, indeed photographed (see picture below), and thus controlled at a lesser cost than through military campaigns. In the summer of 1898 some large 'rebel' groups in northern Taiwan had indeed surrendered. However the rebels in the south remained distrustful of the Japanese motives behind the change of policy and none had surrendered. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Consequently, the Japanese authorities sent more powerful and influential emissaries, such as the very astute and affluent Takao businessman Chen Chung-ho (the patriarch of the still exceptionally powerful Chen family of Kaohsiung, who is pictured on the right), to induce Lin Shao-mao to negotiate terms with the Japanese rulers. However, the one reputedly who persuaded him to surrender was Yang Shih, the adoptive father of one of his minor wives. Lin Shao-mao gave 10 conditions for surrender to the Japanese which are listed below. These conditions the Japanese duly accepted and Lin formally agreed to surrender on 12 November 1899.The terms, as listed below, essentially allowed Lin Shao-mao to act as absolute ruler of his men; to carry arms; and to be exempt from taxation. All the conditions were acceded to in exchange for his simple acceptance of the suzerainty of the Japanese authorities. However, his followers had their names, and those of their immediate relatives, recorded; all their weapons were recorded and marked; and all surrenderees were photographed (see picture below). They and their families thus became 'marked men'. |

Chen Chung-ho ( 1853 - 1930 ) Patriarch of the Kaohsiung Chen family |

||||||||||||||||||||

The ten conditions were as follows:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

The official

surrender ceremony was held at A-hou on 12 May 1900.

One day before the ceremony Lin Shao-mao came down from his hideaway. His first act was to make a donation of 300 silver dollars to the temple of Ma-tsu. He then held a large banquet at his ancestor's house outside the East Gate. The banquet had all the appearance of a hero's homecoming. The following day Lin Shao-mao attended the surrender ceremony accompanied by a retinue of 36 of 'his subjects'. He was able to act for all the world like a king in front of the local people and the Japanese. As a sequel to this surrender ceremony, in October 1900 Lin Shao-mao was formally received at A-hou by Governor-General Kodama Gentaro who was making an inspection tour of the south. Kodama wished to show his sincerity to Lin Shao-mao. This gesture was successful in inducing many other 'rebel' leaders in the previously unruly south to surrender. |

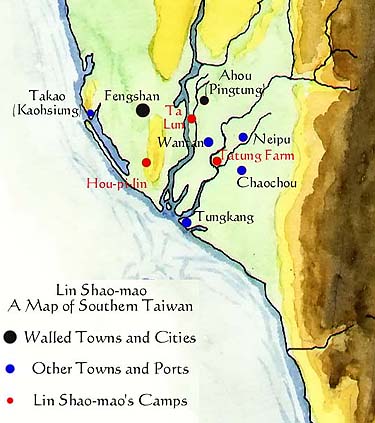

Detail of map of southern Taiwan in Lin Shao-mao's time |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| What happened to Lin Shao-mao after his surrender is described on the next page | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||