|

||||||||||

|

The Japanese colonial powers set about subjugating the mountains areas, bringing to bear an administrative and military capability that had never been witnessed before. Formosa had gained an international leadership in the camphor trade and the Japanese were determined to gain absolute control over this enterprise as well as the burgeoning Hinoki timber business. This strategy put the new rulers in direct conflict with the fiercest 'guardians' of the mountains : the Atayal.

|

Lumbering operations in the hinoki forests on Mount Alishan Photo : Kirkasoff (Click on image to enlarge) |

|||||||||

|

Immediate subjugation was achieved by sending Japanese expeditionary forces armed with carbines into the mountain areas to fight with an elusive enemy armed only with knives, spears and a few matchlock firearms. Apparent victory came quickly to the invaders despite the ravages of dysentery and malaria.

The Japanese quickly established schools not only to inculcate Japanese virtues into the minds and homes of the children but also to identify the worthy student who could be a future administrator of his people. One such student was the son of Chief Rudao Bai. The student was called Mona Rudao and this fact plus the Japanisation of his sister Terwaser (see below) possibly put in place the train of events that lead to the fateful day of 27 October 1930 known as the Wushe Incident.

Mona Rudao proved to be an excellent student and was one of only 18 Aborigine secondary school graduates recorded throughout the Japanese Occupation up to 1940. In recognition of his intelligence and mindful that he was the first son of a comparatively important chief, the Japanese arranged for Mona Rudao to visit Japan in 1910, where his linguistic ability must have enabled him to communicate freely with the people. |

||||||||||

|

While Mona Rudao was away in Japan the Wushe Affair of 1910 took place. There had been many recent incidents to incite the Atayal against the Japanese but the fundamentals remained the same. The Atayal lands belonged to their ancestors with some areas being sacred and others traditionally marked out for family use by buried rocks. To the Atayal it did not matter if the intruder was Hok-lo, Hakka, Japanese or another tribe : the land was in their trust and to be defended at all costs. In this case the Japanese learnt of the planned insurrection by the Atayal against arbitrary land seizures and some 50 braves were killed in a pre-emptive strike. |

|

|||||||||

|

A group of Atayal braves in 1920 (from Owen Rutter's 'Through Formosa" 1923 Photo : J B Montgomery McGovern |

||||||||||

|

The Japanese ferocity can be traced to the very earliest days of the occupation in 1897. At that time Japanese scholars and adventurers were busy exploring, mapping and documenting the new colony.

In 1897 a Japanese military officer was escorting a large group of adventurers to the Central Mountain Range when they were attacked by Tolokku braves. Many were killed including the Japanese officer. Ironically the Japanese then used the Mahebo, Mona Rudao's social group, to exact revenge upon the Tolokku. |

||||||||||

|

Photo : Takekoshi 1907 |

||||||||||

|

After Mona Rudao's return to Formosa in 1910 little is known until 1920. In that year the Salamao Atayal braves were discovered to have hatched another plan to attack the Japanese. In the course of the investigation the involvement of Mona Rudao in the planning was discovered by the Japanese. Mona Rudao was placed on a 'Watch List' and his movements thereafter monitored.

In 1924 there was another aborted attempt to stand up to the latest colonialists. An attack was planned at a major festival in Puli which many mountain police and Atayal communities were scheduled to attend. This time the plotters learnt of their betrayal by the Tautau community before the Japanese. The attack was postponed but the Atayal warriors had learned to be more watchful. |

|

|||||||||

|

Atayal warriors guarding the denuded mountain slopes Photo : Rutter 1920 |

||||||||||

|

After pacification the Japanese authorities had posted Japanese policemen to each community within the 'pacified' highland areas. Each community - usually little more than a single village - had one chief, and the Japanese policemen were exhorted to 'take as a wife' the daughters of these chieftains. In such a way the authorities believed they could create blood ties to the unruly mountain people and thus avoid the risk of insurrection. |

||||||||||

|

The daughter, Terwaser Rudao, married the Japanese policeman for the district. This would have been considered a great honour for Chief Rudao Bai's community, the Mahebo. The daughter thus took a Japanese name and since the local policeman had extensive jurisdictional powers the family influence was greatly enhanced.

However sometime after the wedding the policeman was abruptly transferred to Hualien on the East Coast of Taiwan, while the young bride waited to join him. The call never came. The young wife, now with a Japanese name, was obliged to return again to her family home. Terwaser Rudao had become one more bride abandoned by her Japanese husband. |

|

|||||||||

|

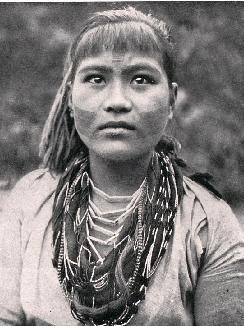

Photo : Kirjassoff Although not a picture of Terwaser Rudao this is taken at that time (1920) |

||||||||||

|

|

For the Atayal honour was everything and a man needed to show that he could defend the honour of his tribe.

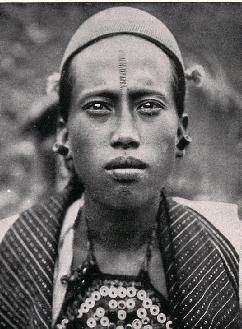

The photograph on the left taken in 1920 shows an Atayal brave upon manhood. The tattoos on his forehead are clearly visible and reflect on his bravery. The incisions show that this brave has taken human heads in 'battle'. In the early part of the 20th century it was still necessary for Atayal men to prove their bravery by taking a human head before they could marry.

Whether such head-hunting would occur in true battle was another question. However no greater feat could be recognised than the taking of the heads of those who dishonoured the family and encroached on the sacred land of the ancestors.

|

|||||||||

|

Atayal brave Photo : Kirjassoff 1920

|

||||||||||

|

"For the Atayal the collection of human skulls was a matter of civic pride" ( Kirjassoff)

|

||||||||||

| Background continued from Previous Page | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||