|

||||||||

|

The opium poppy was introduced into the Orient in the early centuries of the Christian era, by Arab traders from the Middle East. The therapeutic virtues of opium were known to Chinese doctors and the drug was used by them for centuries before the practice of smoking opium made its appearance. This practice spread in conjunction with the adoption of tobacco smoking and the introduction of the tobacco plant into the Far East by the Spaniards.

In the 17th century the practice of smoking tobacco-opium mixtures (madak) first took root on Java in the Dutch East Indies, from where it was spread to Formosa by the Dutch as a treatment for malaria. From Formosa the habit of opium smoking spread to Fukien and the Chinese mainland during the latter part of the17th century. The smoking of opium has been a peculiarly Chinese problem, with the habit spreading extremely quickly in China and amongst Chinese migrants in other Far Eastern countries. In some parts of Southern China and amongst overseas Chinese in South East Asia more than one tenth of the population were habitual opium users, make the addiction almost as common as tobacco addiction is today. |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

In 1729 the first Edict Reports reach Peking of the evils of opium smoking, such as the shrivelling up the features and premature deaths, in Formosa and Fukien. As a result the Emperor Yung Chen in the same year prohibited the sale of opium for non-medical use and the operation of smoking houses, although enforcement proved difficult.

In 1796 opium was again banned throughout China and once more in 1800, at penalty of death. Yet even executions had no great effect on the number of users. Imports increased greatly in the following decades as foreign trading houses seized on the opportunity by growing or purchasing ample supplies in Bengal, British-India and shipping the opium to Canton, South China. In 1839 troops of the Chinese emperor attacked British traders operating near Canton and the 1st Opium War began. China was defeated in 1843, and the Ching Court was forced to accept the terms of a trade that included the importation of opium.

|

||||||||

|

The opium clipper 'Sea Witch' (Click on the image for more on these ships) |

As trade with China increased so did competition. Speed became desirable in the cargo ships; not only to bring the cargoes of opium and especially tea to port, but also to outrun both customs and pirates.

From 1845 the Americans and later the British started to build perhaps the most beautiful and swiftest 'tall ships' ever to grace the seas; the clippers. The design for these thoroughbreds came from the earlier Baltimore Clippers (link) that had outrun the British ships during the Second War of Independence (War of 1812). |

|||||||

|

The clippers, which were built for speed, could sprint at 20 knots

and cruise at 16. Perhaps the most famous of these were the 'Cutty

Sark', a tea clipper that can still be seen in London, and the 'Sea

Witch', an opium clipper that sailed in 1849 from Canton to New York in

81 days, halving the existing record.

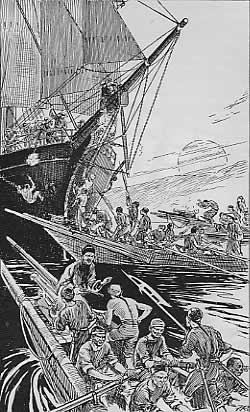

The opium clippers were not only swift, they were also well-armed, mounting from 6 to 10 eighteen pounders. These armaments were necessary to see off the numerous Chinese pirates, who, in their fast lorchas, were attracted by the rich cargoes of silver and opium. The opium clippers sped up and down the coasts delivering opium to, and collecting silver from, the 'receiving ships'. These hulks, heavily armed and fully manned by Manila men, were anchored in the open ports as depots. |

Chinese pirates in lorchas attacking an opium clipper |

|||||||

|

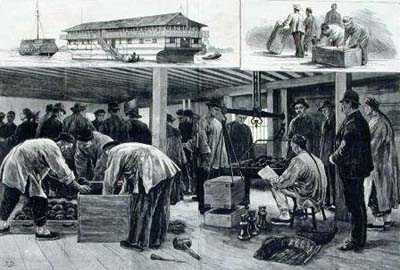

Opium trade conducted on a receiving ship |

The opium market grew steadily on Formosa. In the late 1850s an Irish American called Mooney anchored a receiving ship in Takao harbour to receive opium from his swift fleet of clippers. The actual sale of the opium was entrusted to Chinese 'shroffs' who boarded the receiving ship and handled the accounts. The shroff, or comprador, would arrange for the payment of Likin or other taxes, and also for the purchase or barter of other goods for the return voyage. |

|||||||

|

From Formosa the

clippers returned to Macau or Hong Kong with silver and often camphor.

Other exports from Takao in the mid 19th century were sisal hemp,

turmeric and deerskins, but the most important was to be camphor.

The camphor would probably be loaded onto a cutter at a small port, such as Go-che, up the coast in order to evade the Ching Camphor Monopoly's taxations. The vats of camphor would then be transshipped either to the receiving ship or directly to the clipper at Takao. |

Taipan, comprador and Patna opium balls |

|||||||

| Under the 1858 Treaty of Tientsin, that concluded the Arrow or Second Opium War, the importation of opium was legalised and Formosa was opened up to foreign trade. By 1864 Takao had been officially opened to foreign residence and trade. This expanded trade further loosened the already weak grip of the Ching Customs Authority and led to steady decline in the price of opium. Although a taxation system was set up in Kuang Hsu 7th year, or 1881, it was little more than an attempt to divert some of the immense opium profits to the Emperor. | ||||||||

|

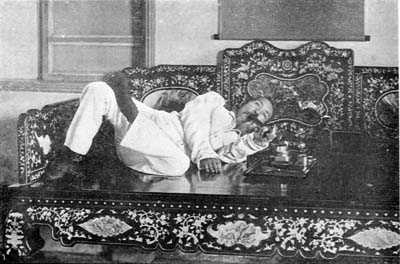

In the popular imagination, opium-smoking was the preserve of the

'literati', or the educated mandarin class.

To a certain extent this was true. After a prolonged evening meal, the mandarin would retire to his purpose-built opium couch (see picture on right) to smoke his opium pipe and perhaps discuss ephemeral matters with his friends. |

|

|||||||

|

|

The Chinese in Formosa seemed particularly susceptible to the comforts

and addictive qualities of opium-smoking. By the end of the 19th century

it is estimated that there were over 200,000 habitual opium-smokers on

the island, with thousands more occasional smokers.

Since the population of Formosa before 1900 was less than 3 million, it can be surmised that over 20% of the adult male population was addicted to opium. |

|||||||

| Such was the situation that confronted the Japanese colonists when they arrived in 1895 to rule the island that had been ceded to them by the Ching Court under the Treaty of Shimonoseki signed on 17 April 1895. | ||||||||

|

||||||||