|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Heyday : 1870 - 1895 |

||||||

| ShaoChuanTou's era of prosperity lasted through the 1870s and 1880s, but its end for Western traders was effectively to be signalled by the 1895 Japanese annexation and occupation under the Treaty of Shimonoseki. | ||||||

|

Although the

camphor trade, that had promised illusory riches in the 1860s, would eventually

blossom in the 1890s, it was the export of sugar that

was to bring riches to the Takow traders in the intervening years. Yet those

same riches were to bring

suffering to many of the local population, and cause a major problem for the

Japanese colonialists, as the British traders sought to balance their

trade through the sale of the pernicious opium into the local market.

Sugar Trade The sugar trade had existed from Takow for many years, with the most lucrative export being to Chefoo in north-eastern China. However, a small trade in brown sugar had opened in 1868 with Yokohama, Japan, following the liberalisation of trade restrictions in that country. By 1871 the export of 'Takow Brown' had trebled to be worth over one and a half million (Mexican) dollars: half of this export was now to Japan. |

||||||

| 'Takow Brown'

was a semi-refined product.

According to Dr W W Myers' contemporary account, Takow brown was produced under extremely basic conditions. The cane was first crushed in temporary sugar mills, consisting of little more than two sizeable granite cylinders turned by oxen-power. The whole mill was covered by a straw thatching supported by a bamboo framework to protect it from the vagaries of the weather during the harvest period. The photograph on the right, showing a typical southern Taiwan sugar mill in Ching Dynasty days, is taken from 'Story of Taiwan Cane Sugar' published in Chinese. (Click on the picture to enlarge). The juice was drawn off through bamboo channels and then boiled to remove excess water in an entirely haphazard manner. The resultant concentrated liquor, albeit unfiltered and full of cane fragments, called Takow Brown, was then made available for sale and export. |

A Thatched Oxen-driven Sugar Mill (Click on picture to enlarge) |

|||||

|

Regardless almost of the quality, the proximity of Taiwan and the burgeoning wealth of the Japanese consumer ensured a steady demand in Yokohama from the Japanese refiners. As a result, given the remarkable fertility of the south-western Formosan soils, the agents and traders enjoyed a good living in Takow, though always dependent on the vagaries of the weather during the lengthy growing season, of up to 16 months, of the sugarcane. |

||||||

|

Formosan Sugar Worker |

||||||

| However the burgeoning exports of sugar meant a fast-developing negative balance of trade at Takow in the early 1870s with thousands of silver dollars beginning to accrue in southern Taiwan, principally in the hands of the compradores and millers. | ||||||

|

Despite the wealth accruing, it seems that little investment was made to

improve the manufacture process. George Kerr states that in 1896

production and extraction methods were little different from those

during the 17th century Dutch period.

Indeed the economic system conspired against this. Sugar was the tenant farmer's cash crop, but he relied upon the local mill to process his crop. This in turn led to the miller becoming the nexus between the market, the landlord and the tenant. The supposed wealth in the farmer's field was to tempt him into seeking advances from the miller. These tended to be loans with exorbitant interest rates secured by the farmer's tenancy right. It was merely a matter of time before many farmers became hopelessly indebted, and the miller a mere financier. The trade figures strongly suggest that the British quickly sought to balance this trade with ever greater imports of opium. It should be noted that in the early part of the 1870s, sugar made up fully 90% of the exports, whereas opium made up fully 90% of the imports. |

An 1868 Mexican Silver Dollar showing Chopmarks from the China Trade (Courtesy Sycee-on-line) |

|||||

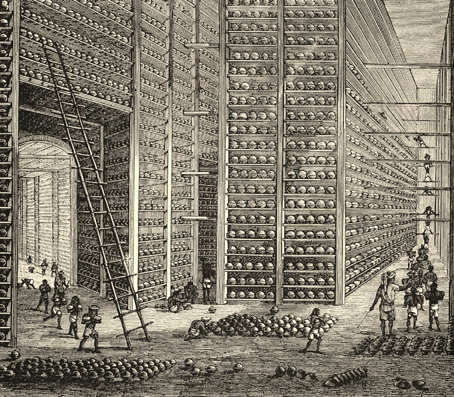

A British Opium Warehouse in Patna, British India |

The

British had seemingly unlimited reserves of opium at hand in their colonies

and vassal states in British India.

Although the British East India Company, the "Honourable John Company" which effectively controlled the trade of India on a charter dating back to 1600, had supposedly backed out of the trading of opium to Canton and China, it remained utterly willing to promote sales from India where they held a production monopoly. Indeed this revenue was necessary to support the operation of a de facto colony of Britain. The East India Company may have lost its control of India in 1857, following the Indian Mutiny, but it remained a powerful force through to 1874 when it was formally dissolved. However the British trade of principally Indian opium to China was not to stop until 1917. It is clear that then, as today, the major revenue-payers have inordinate influence on government policy. This element of financial necessity was something not lost on the later ardent students of colonialism, the Japanese, who would tout Taiwan as a model colony. |

|||||

|

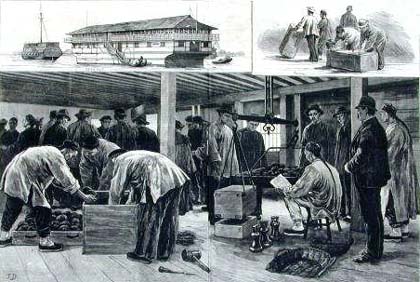

Transported to Taiwan upon the fast opium clippers which could easily

outrun and outgun the local pirates, the opium was typically stored on

'receiving ships' for security.

Upon the receiving ships, actually hulks of decommissioned warships, the opium was traded to the local shroffs or compradores in exchange, at least initially, for silver. The silver unit of choice was the Mexican dollar. This the shroffs could apparently test with their long little finger nails to hear the true ring of silver. The coins were also assayed for quality and then 'chopped' with a metal die by the agent. A fine example of such a coin may be seen in the distinctive image above from the personal collection of Steven Tai, whose www.sycee-on-line.com website has a wealth of information. Such coins can be obtained around Asia or on e-Bay, but one should be very aware of the ease of fakery for silver. |

Sale of Patna opium from a receiving ship |

|||||

|

In the

earliest days the foreign residents had tended to congregate on Chi-hou,

partly because that was where the actual village of Takow was, and

partly because they had been shut out by the 1860 purchase by Dent &

Co of virtually all the shorefront at ShaoChuanTou. However in 1879, the

Customs Commissioner, by then ensconced in the old Shui-lu (Brown &

Co) building at ShaoChuanTou laconically noted in his Customs Report

that he expected the gradual shift of foreign residents to the north

side of the lagoon, at least to escape the unsanitary overcrowding at

Chi-hou.

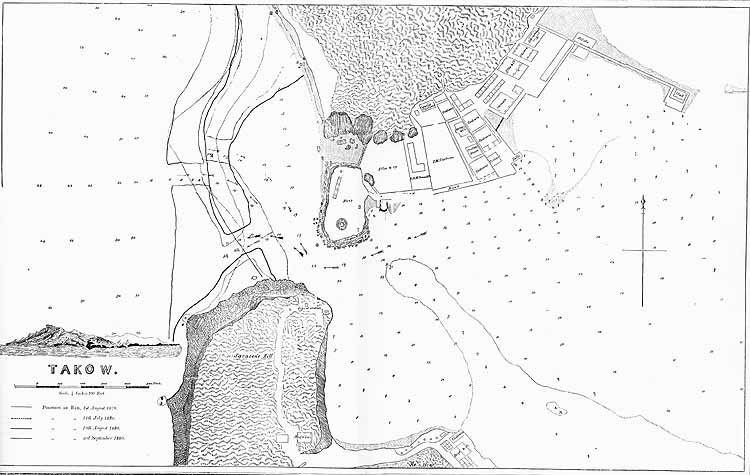

This raises the issue of the British Consular Residence. The ICMC map of 1880 (see below) clearly shows the British Consular Offices but equally clearly shows no consular residence on the hill. |

||||||

|

1880 Imperial Chinese Maritime Customs map of Takow (click on image to show ShaoChuanTou detail) |

||||||

|

The ICMC map above is focussed on the problem of the Takow Bar, which the advent of British steamers, with their deeper draught, in the mid 1870s had highlighted. The sandbar was basically formed by the sand and silt drifting up from the south with the southwest monsoon: this drift had in fact created the narrow spit of land on which Chi-hou lay. The gradual flow of waters out of the lagoon caused the bar to form just outside the narrow harbour entrance. The deeper draught of the steamers increased the difficulties of crossing the bar. This was eventually to divert most of the import trade (primarily in British carriers, and primarily opium) to the port of Anping, which was close to the larger markets and better communications of Taiwan-fu (Tainan). Despite the golden prospects for, and the swelling revenue accruing from, the port of Takow in the 1870s and early 1880s, the Ching authorities, in their local guise as the Tao-tai (Circuit Intendant), failed to respond to the situation. Little investment was made to improve either sugar production or port facilities. As a result, the trade shifted back to Anping which allowed at least a more direct intercourse with the governing authorities. The problem of travelling between Takow and Anping was further alleviated by the opening of a telegraph line in 1877. |

||||||

|

By the late 1880s most of the

foreign traders were resident there despite the fact that the German

carriers, reliant upon the smaller sailing ships due to their lack of

access to coaling stations, continued to frequent Takow. Among the firms

that persisted in Takow was that of Julius Mannich, who had started as

an agent for Brown & Co in 1873, set up his own company in 1879, and who was to remain at Takow until

the 1890s.Anping traders became

dismissive of Takow due the problems of crossing the sand bar lying

outside the harbour entrance and, interestingly, of the 'bad air' from

the numerous sulphur springs in the close vicinity of ShaoChuanTou

(Clark).

It should be noted that Taiwan was made a separate province in 1884 with Liu Ming-chuan being appointed as its governor. Liu proved a very modernizing governor and instigated not only the railway and postal systems on the island, but also modernised its defence in view of the French threat. More significantly, Liu also developed plans for the improvement of Takow Harbour. Sadly, once the French threat was removed Liu was deemed not necessary and left the island shortly thereafter, a victim probably of vested interests. |

Liu Ming-chuan |

|||||

| As has been noted above, the sugar exports, in the form of Takow Brown, began to boom in the early 1870s reaching a peak in 1874. This burgeoning trade attracted the interest of the British government who approved a plan for the construction of a new consulate in 1878. The resulting two buildings are believed to be the British Consular Offices shown on the ICMC map, probably built in 1879, and the British Consular Residence which was probably built a little later around 1882. | ||||||

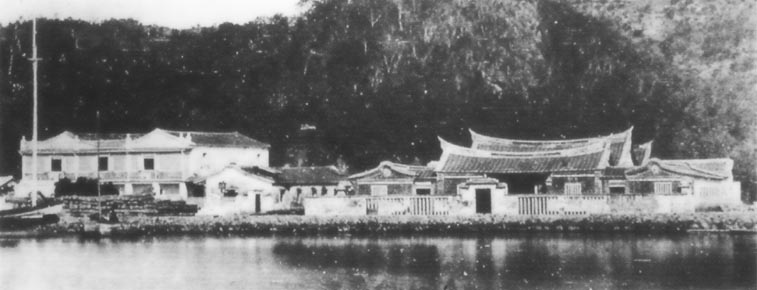

Elles & Co (left) and the Chinese godown |

||||||

|

One of the major traders at this time was Jamieson Elles of the

Amoy-based Elles & Co: a company that had been in operation in Takow

since the mid-1860s. Jamieson Elles was clearly ambitious owning and

purchasing various plots and buildings during the late 1870s, including

the imposing offices to the left in the photograph above.

In 1880 new heights were scaled in the sugar trade, enabling the confident Committee Members of the local clubhouse, called the Takow Club, to successfully offer debentures for the club. |

||||||

|

Heading on the Takow Club Debenture Offer |

||||||

|

However, 1880 for several reasons remained a peak not to be scaled again

until the early 1900s. The early sugar export trade had relied partly on

a strong demand from Australia, but the merging of two competing

companies there led to the abrupt cessation of trade in 1884, leaving

Takow almost fully dependent on the Yokohama market in Japan for exports

by 1887. The 1884/5 blockade of Taiwan had a further effect in that

little cane had been planted resulting in a poor harvest in 1886. This

in turn led the Yokohama traders to tighten their grip on sugar

supplies.

The heady heights of 1880 were to cause trouble for Elles & Co. By 1883, Elles was already in financial difficulties and collapsed shortly thereafter. His business was taken over by AW Bain & Co, run by Allan Bain who had come to Takow as early as 1866 to work as an assistant in Elles & Co.. He appears to have remained very successful and was still in Takao in 1908 when his company rented the British Consular Offices at ShaoChuanTou. |

||||||

| Et

Cetera

Among the British Foreign Office documents on Taiwan is the 1893 marriage at Takow of James Russell Brazier to Helen Eliza Jane Myers: he was 33 years old, she was 19. Brazier had been stationed at the Imperial Chinese Maritime Customs in Takow from 1880 through to 1892, so he had presumably known Miss Myers, the daughter of Dr William Wykeham Myers, since she was 6 years old. As Dr Myers gave his 'full consent' to the marriage in January 1893 one can only guess that Brazier came back expressly for the young girl the same year. Brazier seemingly had a highly successful career in the Chinese Customs and accumulated an important collection of Chinese documents. After he had retired to Bournemouth many of his Chinese manuscripts, including an invaluable volume of the Yongle Dadian, were gifted to Aberdeen University, where he had studied and his father had been a chemistry professor. It is believed that Brazier died in 1926. This marriage was followed in February 1895 by another very noteworthy wedding. This was the marriage of Robert John Hastings to Huang Yun-kuan, which was certainly a very early example of the marriage of a British citizen to a Chinese national under the 1890 Foreign Marriage Act. Hastings had apparently been married to Ms Huang since 1871 and had had eight children by her, the eldest of which, Harry Hastings, was already a prominent trader by 1895 and remained active in the sugar trade well into Japanese times, becoming the manager of the South Formosa Trading Company. The family later came to light again concerning the legitimacy of the offspring prior to 1895. This was referred to the Foreign Minister of the time, who laconically replied that if they could show the earlier 1871 wedding to be under 'lex loci' (local law), then there was no objection. Another notable character, for whom I have unfortunately not found a photograph, is Captain Hermann Vosteen. Vosteen first arrived in Takow as the boatswain of the Eliza Mary which made numerous trips between Amoy and Takow carrying opium and other goods. Oddly, Vosteen decided to stay in Takow in 1869 and the Eliza Mary foundered off the Takow coast in 1870. Vosteen was one of two pilots in Takow and later commanded the steam tug Sin Taiwan, which was involved in many a rescue. The Sin Taiwan had originally belonged to a Claus Krohn who, according to Otness, 'died off Anping in 1879 and was buried in the Foreigners' Cemetery at Kaohsiung'. A later incident concerning the wreck of the British schooner 'Chingtoo' on the bar of Takow was to lead to the suspension of Vosteen's pilot's licence. He seems to have left his home in Chi-hou in 1877, selling to a Parsee trader, and moved up to Tainan. |

||||||

|

The Legacy

As the sugar trade subsided, becoming dominated by the prices in Yokohama, many of the traders moved on. However, in their wake they were to leave a massive problem for the Japanese. As mentioned above, opium had been the preferred means of payment for the sugar. Thus the Chinese compradores had spread the habit throughout southern Taiwan through their sugar networks. The difficulty of finding a Chinese wife in an area where Chinese men outnumbered Chinese women by ten to one and the initial reticence of the casual labourer from Fujian to taking a native wife, as he believed he would return to China, had a strong effect: most young men sought solace in the opium pipe. A day's salary would be spent on an evening's smoking. The result was that perhaps 25% of adult males in south Taiwan were addicted to opium by 1895. It was a problem that the new Japanese rulers would have to face. (see The Opium Files on this site) . |

||||||

|

The squalour of the poor man's opium den |

||||||

|

||||||