|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Loss of the Benjamin Sewall |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On Friday, 10 October 1903, a despatch arrived at Lloyds, London, from An-ping, Formosa, stating that, "The American ship Benjamin Sewall and her cargo has been lost at the Pescadores." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Introduction

This webpage looks into the story of the ship Benjamin Sewall (shown in an old oil painting on the right), considered one of the finest of the majestic square riggers that once sailed the oceans powered by the wind and currents alone. The saga of her long final voyage from North America via Australia to Taiwan (Formosa) is related. In particular, the final days of the ship Benjamin Sewall and the fate of her crew are detailed. What is for certain is that she was not wrecked at the Pescadores (Peng-hu), but met her fate some 200 miles to the southeast near the island of Botel Tobago. The foundering of the Benjamin Sewall was to bring upon the islanders precisely the attention they had sought to avoid. |

Painting of the Ship Benjamin Sewall (Bowdoin College, Brunswick) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ship Benjamin Sewall

The ship Benjamin Sewall was built at the shipyard of Pennell Brothers near Brunswick, Maine, in 1874. The Pennell Shipyard had been building wooden vessels for nearly 100 years, and the Benjamin Sewall was the largest and last of these famous Pennell vessels. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

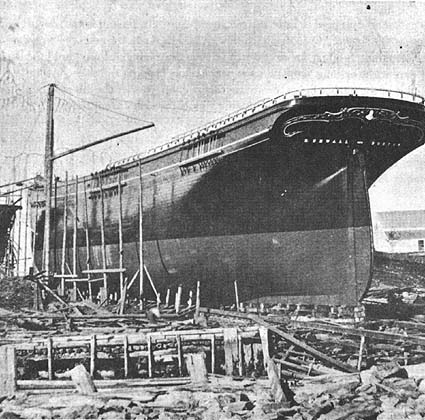

The Benjamin Sewall on the ways at Pennell's Shipyard (Courtesy Pejepscot Historical Society, Brunswick) |

The ship, with her fine sturdy lines, is shown in the photograph on the left on the 'ways' (slipways) at Pennell Shipyard. Her name, here given as B. Sewall - Boston, can just be seen on her stern. The specifications of the 3-masted square rigger were registered as: length - 202 ft; breadth - 39 ft; depth - 24 ft; with a gross tonnage of 1433 tons. This was about the average size for the square riggers of her time. The Benjamin Sewall was launched from the 'ways' on 27 October 1874, in the presence of the 80-year-old Benjamin Sewall, the prosperous Boston businessman after whom she was named, and whose bust can also be seen in the photograph adorning the scroll on her stern. She could carry around 2,000 tons of cargo, and could stow just over a million board feet of sawn lumber and timbers. Though not a fast boat, the Benjamin Sewall had her moments, once making 336 miles in a day's sailing. Her masters regarded her as a stout ship who handled well. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Her first master was John Pennell under whom she five times rounded Cape Horn. On one voyage she sailed to the Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru to load guano (see the Robert Bowne Story on this site). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| While

off Huanillos Island on the evening of 9 May 1877, the Benjamin

Sewall

experienced first the violent shaking from an undersea earthquake, and

then a terrible tidal wave. After a night of aftershocks, combusting

rock falls and surging waters, all to the sound of colliding boats and

drowning men, the dawn showed the extent of the damage.

The shore settlement had been almost entirely swept away with hundreds drowned, and, of the 23 vessels anchored in the roadstead, 5 were lost and 15 badly damaged: amongst these was the Benjamin Sewall. Yet, after extensive repairs at the nearby port of Callao, the Benjamin Sewall loaded her guano cargo from another guano island, Pabelon de Pica, and sailed round the Cape to Europe. Captain Pennell had struck his head during the earthquake and suffered from severe headaches during the onward voyage around Cape Horn to Europe. After discharging his cargo of guano at Brest, France, Pennell was joined by his wife, Abby, and their two sons, who joined the ship. Proceeding first to Cardiff, Wales, to load a cargo of 2,000 tons coal, the Benjamin Sewall sailed for Rio de Janeiro. Throughout the voyage to Rio, Captain Pennell's headaches worsened and he was taken to the hospital upon arrival. There, at Rio de Janeiro, the first Master of the Benjamin Sewall, John Pennell, died on 5 July 1878. |

John D Pennell (c.1830-1878) (Courtesy Robert Coffin Jr) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Following the death of Captain Pennell, the ship resumed her travels on around Cape Horn and up to Callao under the command of her Chief Mate, William Ryan. Ryan was the nephew of Samuel Sewall, the managing owner of the Benjamin Sewall. The command of the Benjamin Sewall thereafter alternated between Ryan and his uncle Samuel Sewall, who had also sailed on her maiden voyage across the Atlantic. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

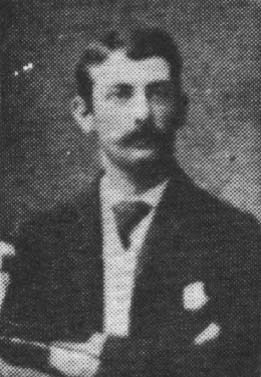

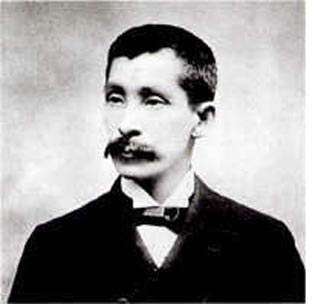

Arthur M Sewall (28 January 1867 - 22 September 1939) (Courtesy Phillip Sewall) |

In 1888, Samuel Sewall appointed his 21-year-old eldest son, Arthur M

Sewall (shown in a contemporary photograph on the left), as Master of

the ship Benjamin Sewall. It is probable that the Benjamin

Sewall had been extensively overhauled prior to this appointment.

Arthur Merrill Sewall was born in North Edgecomb, Maine, on 28 January 1867. After crossing the Atlantic on board the Benjamin Sewall at the age of 12 with his father, Arthur Sewall had shown little interest in schooling on the shore. In 1882, aged 15, he had run away to sea and by the age of 21, in 1888, he had his Master's papers. On his first voyage as master, Captain A M Sewall took the ship from Boston to Australia and then on to Valparaiso, Chile. After discharging his 2,000 tons of Australian coal at Valparaiso, and commencing to load 2,000 tons of nitrate for New York, Captain Sewall was struck down with a serious bout of malaria. While in hospital at Santiago he met a captivating young Chilean girl of Castillian descent, Aurora Alliendes of Rancagua. Her family did not wish their daughter to 'marry a gringo', and so the two of them eloped. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arthur

Sewall and his young bride Aurora thereupon sailed away on the ship Benjamin

Sewall together, around the Cape Horn and up to New York.

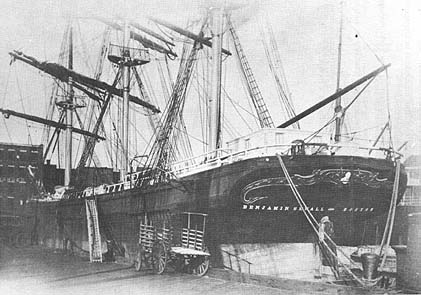

For the next 12 years, Captain Sewall and his wife Aurora made their home upon the ship Benjamin Sewall. The Captain's quarters lay immediately forward of the Chart Room. The Chart Room, which served as a day-room in fine weather, is the structure that can be seen on deck at the stern of the ship in the 1888 photograph on the right. Aurora furnished the cabins with 'fine oriental rugs and lace curtains', and also had a piano and sewing machine aboard. |

The Benjamin Sewall lying at Boston in 1888 (Courtesy Frank Claes) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

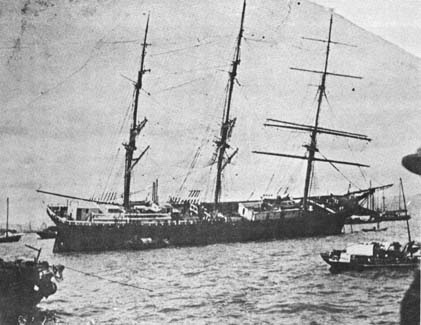

The Benjamin Sewall aground at Hong Kong, November 1900 (Courtesy Mrs C D Petersen) |

While

master of the ship Benjamin Sewall, Captain A M Sewall was to

meet with two great typhoons in the South China Seas. The first was at

Hong Kong in November 1900, when she was driven ashore (see photograph

at left).

The second typhoon was off Shanghai in August 1901. The ship Benjamin Sewall had been swamped and suffered extensive damage. She limped in to Hakkodate, Japan, for repairs. Captain Sewall, still intermittently suffering from bouts of malaria and with a feeling that he was dogged by bad luck, had had enough. After supervising repairs at Hakkodate, Sewall turned the command over to his Chief Officer for the Benjamin Sewall's return leg across the Pacific to Port Townsend, Washington. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Captain Arthur and Aurora Sewall boarded a steamer for Vancouver, British Columbia. From Vancouver they travelled down to Port Townsend where they then lived for the next 20 years. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Last Voyage of the Ship Benjamin Sewall | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

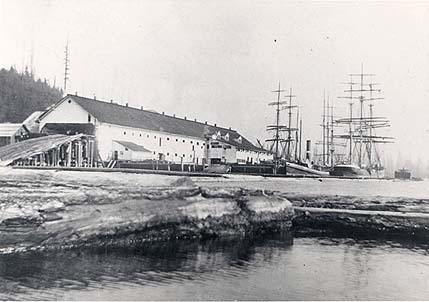

| In

November 1901, the ship Benjamin Sewall set out from Port

Townsend on what was to be her final voyage. She was under charter to a new captain

chosen by Captain A

M Sewall and was bound for Fremantle in Australia, where she was fixed

to deliver a cargo of

Canadian lumber.

The ship had begun her voyage by loading about one million feet of Canadian lumber from the Moodyville Mills in the Burrard Inlet on the North Vancouver shore (see photograph of Moodyville Mills on right). The Benjamin Sewall was then towed back down the Puget Sound to Port Townsend where she took on some six tons supplies and then cleared to sail to Fremantle, Australia. |

Ships loading at the Moodyville Mills in 1897 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

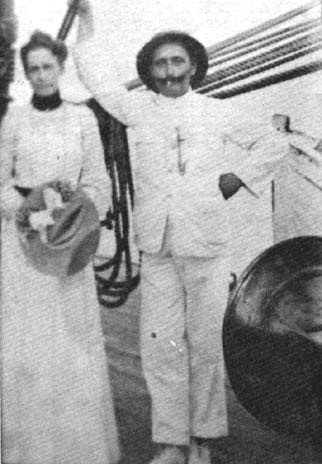

Jack Hoelstad (b. 19 November 1866) and wife May (Courtesy Maybelle Piper Haynes) |

The new commander of the Benjamin Sewall was Captain J H Hoelstad. Jack Hoelstad is shown in the picture below with his wife, May, who travelled with her husband on the ship. Little is known about Jack Hoelstad. He was 34 years old at the start of this voyage, and two months older than Arthur Sewall. His wife's family was certainly from Maine, but he himself may well have been Norwegian. The Benjamin Sewall set out on the afternoon of 3 November 1901, but, after rounding Cape Flattery at the mouth of the Puget Sound, she ran into a series of gales and calms and made slow progress. While the gales would tear away the sails of these large sailing ships, the calms were almost as exhausting. The heavy and powerless vessel would founder and roll her sides under in the troughs of the waves, all the time creaking and groaning as if she would fall apart: sleep became almost impossible. On 27 November 1901 the worst of the gales struck. Yet more sails and part of her deck load of lumber were lost, but worse still the hold remained filled with several feet of water. The Benjamin Sewall had sprung a leak. Captain Hoelstad decided to alter course and head for Honolulu to find and repair the leak. It was a wise decision. As the ship Benjamin Sewall neared Honolulu the situation worsened. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

They spent Christmas Day of 1901 becalmed on the leaking ship within

sight of Oahu. The ship was equipped with a windmill pump to remove the

water: this only worked when there was a wind, in the calm the crew

struggled to stop stabilise the situation. She was now leaking 6 inches

an hour and had 11 ft 6 inches of water in her holds.

On the 27 December they were still becalmed and the leak was gaining on them. However, the next day a fresh breeze sprang up and the ship anchored outside the reef at Honolulu; she was towed into Honolulu Harbour (see picture below) on 30 December 1901. On the ship Benjamin Sewall was Helen Jackson Piper, the 18 years old niece of Captain Hoelstad. Miss Piper (shown right), from Damariscotta in Maine, kept a journal for the voyage. |

Helen Jackson Piper (Courtesy Maybelle Piper Haynes) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Honolulu Harbour around 1910 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In her journal, Miss Piper, freed from the confines of the ship,

describes Honolulu as being 'simply beautiful' with luxuriant foliage

everywhere. She also comments on the 'fine buildings that [had] been

built during the last two years'. In fact, Hawaii had been formally

annexed by the United States just a few years previously, in 1898.

The source of the leak on the ship Benjamin Sewall had proved elusive, necessitating first the tow into port and then a stay of two weeks. However, by 15 January 1902, the Benjamin Sewall was ready to resume her journey down to Fremantle, Australia. Captain Hoelstad was to rue the decision to sail to Fremantle, and vowed not to undertake the voyage again. The journey was to take almost four months to complete, including a month becalmed in the Celebes Sea. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

South Quay, Fremantle in 1899 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The ship Benjamin

Sewall finally arrived at Fremantle on 1 May 1902. It can be

assumed that she berthed at South Quay (see photograph above) to

discharge her cargo of Canadian lumber.

Miss Piper's journal ends upon the Benjamin Sewall's arrival at Fremantle. However, seemingly some 40 years later, Helen Piper added some interesting further detail to her time in Fremantle. Firstly she mentions the arrival of a stricken ship that had lost its propeller whilst carrying horses from Australia to South Africa for use in the Boer War. This ship can be identified as the Boveric, which was towed into Fremantle on 15 May 1902, just two weeks before the end of the Boer War. The Boveric had lost her propeller in the southern Indian Ocean. The chief officer and three of the Boveric's crew had volunteered to take one of the boats and sail to Fremantle for assistance. They covered almost 1000 nautical miles in 26 days before arriving beside the Benjamin Sewall's berth at Fremantle: bizarrely, the Boveric was towed in the very next day. The second noteworthy incident at Fremantle that Miss Piper records is a visit to 'a prominent family' in Perth. She relates that the young son of this family, whom she identifies only as 'Joe', expressed great eagerness to go to sea, and that Captain Hoelstad had signed him up as Third Mate. From Helen Piper's journal we know that the ship Benjamin Sewall, with a young Australian Third Mate and bound for Singapore for the China lumber trade, departed Fremantle in ballast around the end of May 1902. Nothing further is known about the movements of the ship Benjamin Sewall until August 1903, over one year later, though Miss Piper had noted that she was bound to Singapore to partake in 'her great trade in timber with Northern China'. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The End of the Ship Benjamin Sewall | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The ship Benjamin Sewall departed from Singapore on 25 August 1903, carrying a consignment of teakwood for the Chinese port of Shanghai. As this was typhoon season, Captain Hoelstad decided to chart a course to the east of Taiwan. The shallow waters and numerous reefs and shoals of the Taiwan Straits, to the west of the island, were extremely treacherous for a sailing vessel even though few typhoons actually enter the straits. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

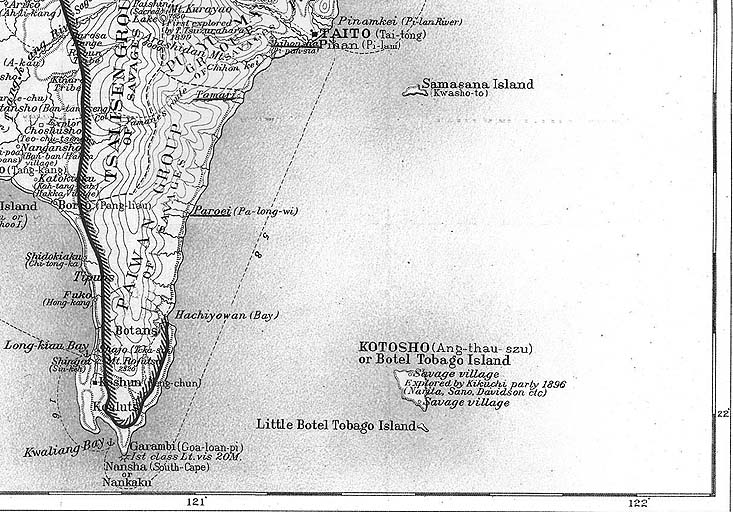

Detail of Davidson's 1901 map of Formosa showing the southern tip of Taiwan and Botel Tobago |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On 4 October 1903 the ship Benjamin

Sewall

passed close to the Garambi (Oluanpi) Lighthouse on the southern tip of

Taiwan (see map of Taiwan/Formosa above). The lighthouse, communicating

with the Benjamin

Sewall, displayed a flag message with a typhoon warning. However,

the flag code being used was allegedly unknown to Captain Hoelstad.

There were soon clear signs of the approaching typhoon: the barometer was falling rapidly, and the wind and sea were increasing. Captain Hoelstad decided to alter course to the south-east to try to avoid the typhoon's path. Given that most typhoons tend to track up the east coast of Taiwan before arching eastwards towards Japan, and that a massive typhoon is recorded as having struck Japan in October 1903, Captain Hoelstad may have made the right decision; however, it was too late. In the early hours of 5 October 1903 the Benjamin Sewall was struck by mountainous seas and hurricane force winds. Her three topmasts, her bowsprit and her rudder were broken off, leaving the ship at the mercy of the elements. The helpless ship rolled heavily with her rails awash, the seas breaking over her and flooding the cabins and the holds. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When the typhoon eased, an inspection of the ravaged ship was carried out. The decks were a shambles of fallen spars, twisted rigging and torn canvas - this could be cleared; but the holds with their cargoes of hardwood were two-thirds full of seawater. Hoelstad believed that, as the water seeped into the wood, the ship Benjamin Sewall would sink. Around noon on 5 October 1903, Captain Hoelstad gave the order to abandon ship. There were 23 persons on board and they all managed to get safely aboard the two lifeboats that remained with a few provisions. One boat was under the command of Captain Hoelstad; the second boat was under the Chief Mate, Joseph Morris. (See below for details of those in each boat). Neither of the boats had fresh water aboard due to the loss of a third boat stocked with provisions as it was being lowered into the seas beside the ship Benjamin Sewall. The Captain's boat was provisioned with some canned pineapple, three cans of milk, some salt meat and a few biscuits; the Chief Mate's boat was in a similar condition with some canned fruit and tinned meat, and a few biscuits. But no water. The southern tip of Taiwan (South Cape) was about 60 miles away to the north-west: in a more northerly direction, and some 35 miles off the Formosan coast, lay the island of Botel Tobago (see map above). |

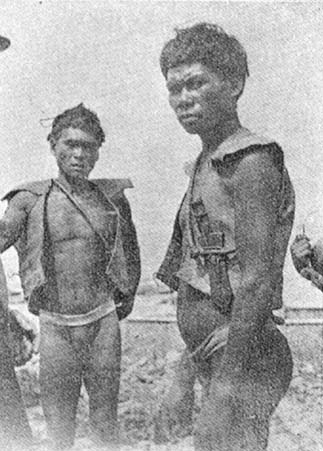

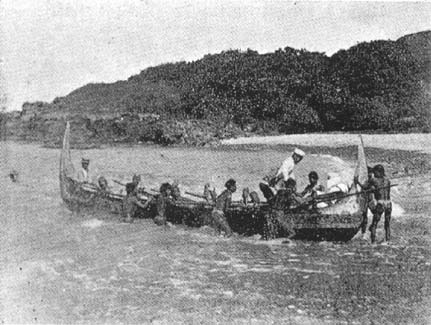

Botel Tobago Natives (from Davidson) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Botel Tobago had gained repute as the 'home of savages and cannibals'; and Captain Hoelstad cautioned his Chief Mate Joseph Morris not to land upon the island under any circumstances. In fact, a few years earlier, in March 1896, Botel Tobago had been safely visited by James W Davidson, then a foreign correspondent, later the US Consul at Taipei. Davidson, from whose superb book 'The Island of Formosa Past and Present' the photographs above and below are taken, reported on a peaceful and isolated people, who neither drank alcohol nor smoked tobacco. He does, however, record some of their history and their past contacts with the outside world. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Botel Tobago boat in the surf (from Davidson) |

In 1722 some Chinese traders had visited Botel Tobago in the hopes of

trade: the islanders were unwilling to part with any of their few

possessions. Not to be disappointed, the Chinese traders thereupon

slaughtered many of the natives and fled back to Taiwan with their

meagre belongings.

Years later a second group of Chinese traders ventured onto the island. The Botel Tobago natives, mindful of what had befallen their ancestors, took pre-emptive action. Not one of the trading party ever returned to Taiwan. As for Davidson, he encountered no such belligerence. But Davidson arrived on a 3,000 ton Japanese naval vessel and was prudently accompanied by a Japanese army major and a detachment of Japanese infantry. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

During the remaining daylight hours of 5 October 1903, the two boats,

sailing and rowing, kept within sight of each other. However, during the

night of 5 October the two boats lost contact and by dawn were out of

sight of each other.

On 6 October the Captain sighted Botel Tobago but gave the island wide berth, soon they spotted the lighthouse at South Cape. The shore offered no safe landing place and night was coming on. Bravely, the Second Mate, Mr Stenke, volunteered to swim to shore for help. Within an hour, lights appeared on the shore directing the boat to a small cove on the cape. Those in the Captain's boat were now safe, but of the Chief Mate's boat there was no sign. It was feared that, despite the dire warnings, the Chief Mate's boat had landed on Botel Tobago. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Data from Egan and US Dept of State Records) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On the following morning of 7 October the Japanese police on Taiwan sent a boat across to Botel Tobago. On the 8th the policemen returned with two survivors from the Chief Mate's boat: a Russian named Reinwald and a Filipino named Salio. They related a harrowing tale that is recorded below: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Upon nearing Botel Tobago Island, the Mate had insisted on landing. When

savages appeared on the beach, they had tried to get away, but were

surrounded by four canoes and a horde of savages armed with knives and

spears. They were stripped of their clothes to the skin, including the

Japanese girl, their watches and belongings taken, then the boat was

overturned. They were about half a mile from the shore. The savages then

left them clinging to the overturned boat. The Third Mate remained with

his wife who could not swim. Then one-by-one the others dropped off, the

Chief mate, carpenter, cook and two seamen. Three Japanese seamen struck

off for shore and they did not know what had become of them. The Russian

and the Filipino, both good swimmers, had managed to reach shore, but

were seized by the savages. Meanwhile they had brought in the ship's

boat and stripped it of all its fittings and equipment.

But a worse fate awaited the two seamen; they were taken into the hills as slaves - still without clothes - and forced to do heavy work of chopping and carrying wood. Without any clothing, their bodies became badly blistered in the hot sun. When found by the police they were more dead than alive. But they recovered. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It should be pointed out that the Botel Tobago islanders tell a rather

different story. They recount that, as they lined the shore to welcome

the lifeboat, someone in the boat, perhaps mistaking their fishing

spears for weapons, opened fire with a pistol. It was, say the Yami,

these shots that provoked the incident.

In any case, this initial report that reached the American consul in Taipei was sufficient to merit a robust response. The US Navy Asiatic Fleet Headquarters in Kobe, Japan, was ordered to despatch gunboats to Botel Tobago. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

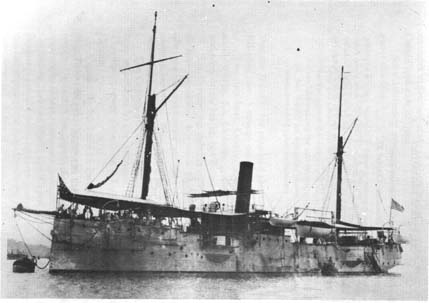

The USS Wilmington and the USS Don Juan de Austria set out

for the South Cape of Taiwan under full steam on 13 October 1903.

The USS Don Juan de Austria had a curious history. She had been part of the Spanish navy and had been sunk on 1 May l898 during the Battle of Manila Bay. She was then raised from the bay, overhauled and refitted at Hong Kong, and commissioned there into the US Navy on 11 April 1900, retaining her original name. This was a clear indication of the intensified American interest in the Far East after the acquisition of its Pacific island territories. |

USS Wilmington |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

USS Don Juan de Austria |

The USS Don Juan de Austria arrived at South Cape on the 17th

October, anchoring beside the USS Wilmington at Kwaliang Bay, the

anchorage just to the west of South Cape.

The USS Don Juan was ordered to proceed to Botel Tobago to discover what had happened to the missing ten persons in the Chief Mate's boat. At noon on the 18th she arrived off the southeast end of the island. A Japanese policemen came out in a native boat and informed the commander, Lt-Com G W Denfield, that three Japanese seamen from the Benjamin Sewall had been found on the 14th October. The edited deposition of one of the Japanese seaman, Yoshize Aoki, is recorded below. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"My name is Y. Aoki. I am a native of Nagasaki, Ken, Kiushu Island, Japan. I shipped at Singapore on board the American Ship Benjamin Sewall bound to Shanghai, with teak. After a three-day's calm we were struck by a typhoon and lost all three masts. The Captain gave the order for all hands to abandon ship. I went in the boat in charge of the Chief Officer. About half an hour before sunset on the 10th we were about [5 miles] from the North shore of [Botel Tobago] when we were attacked by four canoes, each manned by about twelve savages armed with knives. They ran alongside of us and as many as could clambered on board and stripped us to our skins, not even sparing the [Japanese] woman. We all had some money and the Chief Mate, the cook and one of the seamen had watches. They pried off all the brass work, took out the boat plug and capsized the boat. After this they made off. They were with us about an hour. It was now quite dark and we could not see where they went. Afterwards the moon came up. The Negro and the Chinese cook drowned about ten minutes after the boat capsized and about two hours afterwards the Chief Mate let go and drowned. He was an old man and a Norwegian or American. After the Chief Officer drowned, one of the Manilla men and the Russian struck out for the shore, and after them the other Manilla man and the Chinese carpenter. Then we three Japanese started for the shore. The Japanese woman wanted the 3rd mate to go too as she could not swim so far, we were then about [2.5 miles] from the shore, but he said he did not care to leave her. He was an American. We reached the shore and hid among the mountains as we were afraid of the savages. We did not know that there were any Japanese policemen on the Island. We killed a goat and found plenty of fresh water. We suffered from our naked condition and made some straw mats to shield us from the sun. Altogether we slept five nights in the mountains. Then we were found by a party of natives and brought to the police station where we were fed and clothed. We had no arms, only our jack knives." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

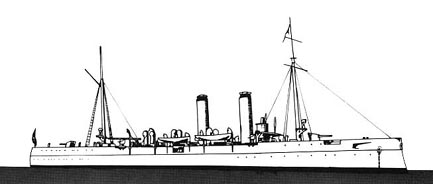

IJN Miyako |

At 3.00 pm on the same day, 18 October 1903, the Japanese Cruiser Miyako

(see line drawing on left),

under Commander S Tochinai, arrived off Botel Tobago. She was

accompanied by a Japanese steamer with twenty policemen

aboard to make a thorough investigation.

Shortly thereafter the USS Don Juan de Austria sailed for Hong Kong to file a report with the US Consul General and await instructions. Captain Hoelstad, together with his wife and niece, had already arrived. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All of the persons in the Captain's boat had survived, but from the Chief Mate's boat there only 5 survivors. No trace of the others was ever found. Among the 7 who perished was the Third Mate, Thomas Pickle. Egan believed him to be the young Australian from Perth, and it makes a poignant tale to believe that he had fallen in love with and married a young Japanese girl. As for the Ship Benjamin Sewall, her fate is unknown. She was spotted the day after she was abandonned by the British steamer SS Oro, and again on the 8th October by the SS Umballa. Both ships tried to tow her to harbour but lacked the power. It was even rumoured that she was spotted again a few weeks later, still afloat on the seas. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Aftermath | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Benjamin Sewall affair became a matter for the US Department of State. On 7 November 1903, the US Vice-Consul at Taipei, Mr A C Lambert, had written to Dr Goto Shimpei, the Chief of Civil Administration in Formosa, requesting further information on the incident, and, in particular, further information about the fate of the Japanese woman married to the American Third Mate. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dr Goto, replying on 17 November, omitted to mention the Japanese woman

but stated that 'this Government have efficiently and strictly censured

[the Botel Tobago islanders], and will warn them not to repeat such

misconduct again in the future'.

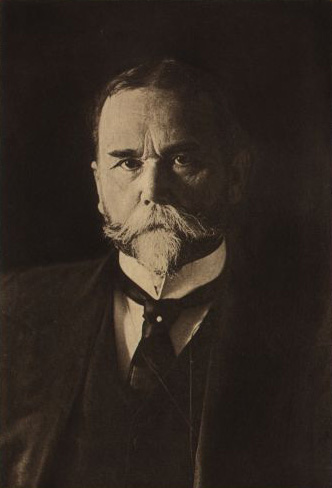

Vice-Consul Lambert was not satisfied with the mere 'censure' of the islanders and referred the matter to his superiors: Francis B Loomis, Acting Secretary of State for Secretary John M Hay (see photo right); and Lloyd C Griscom, the US Minister at Tokyo. On the night of 27 January 1904 a large force of Japanese police was despatched to Botel Tobago. As dawn broke the Japanese besieged the three main settlements on the island, burning 13 houses and capturing 10 'would be guilty ones, including the chiefs and important members of the tribes'. However, many of the islanders had fled into the mountains to avoid capture. The ten captives were taken to the prison at Taitung (Taito, see map above). The Formosan government was having great difficulty in finding those responsible for the capsizing of the Chief Mate's boat, with the resultant loss of seven lives. This was partly due to the lack of any interpreter for the dialect of the islanders, and partly due to the natural reticence of one islander to give evidence against another in such an isolated community. |

John Milton Hay (1838-1905) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice-Consul Lambert submitted to the US State Department three suggestions that might be put to the Japanese Government as a means to preventing such occurrences in future. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First.

That three or four of the principal chiefs of the villages known to be

implicated in the outrage shall be detained as hostages for the good

behavior of their tribesmen for a period of not less than three years,

and that the place of their detention be the jail at [Taipei], where an

opportunity would present itself for a mastering of their dialect by

some responsible officials.

Secondly. That the police force on the island of Botel Tobago be increased in numbers, particularly during the typhoon season when wrecks are most likely to occur. Thirdly. That in the event of any further outrages occurring the hostages be promptly made to pay the penalty. |

Baron Komura Juntaro (1855 - 1911) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| US Secretary of State Hay approved of these suggestions and duly ordered Lloyd Griscom, the US Minister at Tokyo, to place these before Baron Komura Juntaro, the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs. Baron Komura instructed the Formosan government accordingly. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It appears that the Botel Tobago islanders paid a heavy price for protecting their shores from intruders. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

Much of the information above has been taken from a book entitled 'Ship Benjamin Sewall', written by Douglas Egan and published in 1982 by Ye Galleon Press, Washington. For much more on the ship Benjamin Sewall, the reader is referred to Egan's book which, though long out of print, can be easily obtained through Abebooks. The journal of Helen Jackson Piper is contained among her papers held at the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College. Amongst these papers there is also an unpublished account of her experiences on this voyage entitled 'The Girl in the Lifeboat'. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||